Metabolic Flexibility: The Key to Unlocking your Health

Over the last few decades, our health has declined at a rapid rate. Despite living in a time where we have access to more health information than ever before, we are struggling to initiate long-term health change.

As a result, the incidence of obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, sarcopenia, and pretty much any other disease you can think of are at an all-time high.

And for the longest time, there wasn’t an answer.

Until now that is.

See, there have been some very interesting research looking into a new concept known as metabolic flexibility, and it just might hold the key to unlocking your health for good.

What is metabolic flexibility?

In simple terms, metabolic flexibility essentially describes your ability to switch between burning carbs and burning fat as they become available (Goodpaster, 2017; Smith, 2018).

For example, if you have great metabolic flexibility, then you can burn carbs easily when you eat carbs, and you can easily burn fat when you eat fat (or when you don’t eat anything at all). In this manner, you can switch between carbohydrate metabolism and fat metabolism easily and efficiently.

As interesting as this is, you might be wondering what is the role of metabolic flexibility in health and disease?

I mean, I did say above that it might be the key to unlocking your health, right?

Well, as a rule of thumb, those people who have poor metabolic flexibility are at a much higher risk of disease and illness than those who are not. They tend to be resistant to the hormone insulin, and means they are also at an increased risk of diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

Moreover, these same individuals have a poor ability to access stored fats for energy, which means they are also much more likely to be obese.

Not good.

What are the benefits of metabolic flexibility?

The negatives associated with metabolic inflexibility are apparent – but what about the benefits of metabolic flexibility?

Well, first and foremost, being metabolically flexibility will allow you to safely and effectively use all of the foods you eat for energy. This means that you don’t really need to be considered about what you eat so much as how much.

It also means that you can optimize your energy production to perfectly match the exercise that you are currently performing.

For example, if you are running long distances at a lower intensity, then you will easily be able to tap into your fat stores to facilitate sustained energy production. On the other hand, if you are performing a 400-meter sprint, you will also be able to efficiently break down carbohydrates to produce energy in a rapid manner.

In both scenarios, your athletic performance will be optimized.

Finally, if you have good metabolic flexibility, then your body will also be more efficient at using fat for fuel and protein for recovery. This means that if you are metabolically flexible, your ability to lose fat and build muscle is going to be enhanced.

Signs of metabolic inflexibility

With this in mind, I quickly wanted to outline some signs of metabolic inflexibility that you can look for. While these are not any means perfect, they do suggest that you may not be as metabolically flexible as you could be:

- Hard time losing fat, even if you are in an energy deficit

- Get tired after eating a carbohydrate-rich meal

- Can’t go any more than three hours between feedings, or you get uncontrollably hungry 2-3 hours after eating

- Crash after lunch every day

- Can’t function without coffee

- You find yourself feeling lethargic, tired, and grumpy while intermittent fasting

What disrupts metabolic flexibility?

There are several different things that can impact your metabolic flexibility, however, that which appears most significant is your diet – in which it provides a clear link between metabolic flexibility and insulin resistance (Kahn, 2000: Galgani, 2008).

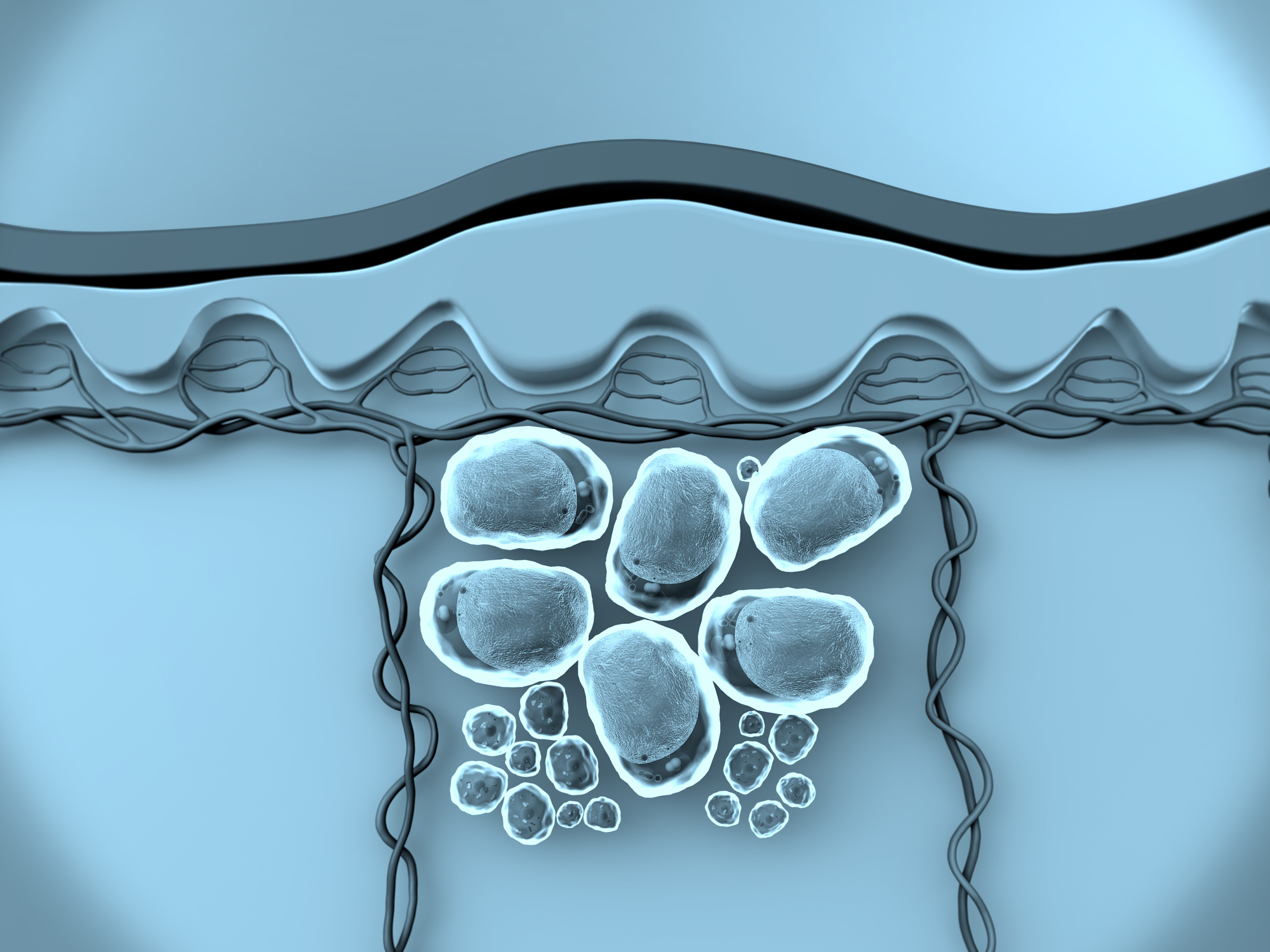

There is a growing body of evidence suggesting that if you eat too much energy or have a diet that is too rich on processed carbohydrates, you are more likely to become resistant to the hormone insulin.

See, when you eat carbohydrates, your body secretes insulin, which causes the uptake of carbohydrates and protein into your cells.

It is actually for this reason that insulin is so important for recovery.

However, if you overeat often (or have a diet that contains a lot of carbohydrates), then your body is going to start secreting insulin chronically. Over time, your body will become resistant to this insulin, in which it will no longer be able to access fats for energy.

This causes your blood sugar to become chronically elevated, and you will become capable of only using carbohydrates for energy.

In short, you will become metabolically inflexible.

Now the scary thing about this is that the standard American diet is a disaster for metabolic flexibility. It is built around heavily processes carbohydrates and has you eating at frequent intervals (think three square meals per day, plus a heap snacking in between).

But fortunately, it is not a death sentence.

How to become metabolically flexible

Given that a loss of metabolic flexibility is ultimately driven by poor lifestyle habits, it stands to reason that it can be improved by good lifestyle habits – and that is exactly what the research suggests!

Metabolic flexibility and exercise

As I am sure you could have guessed, evidence suggests that exercise can play a huge role when it comes to improving metabolic flexibility (Battaglia, 2012; Bird, 2012).

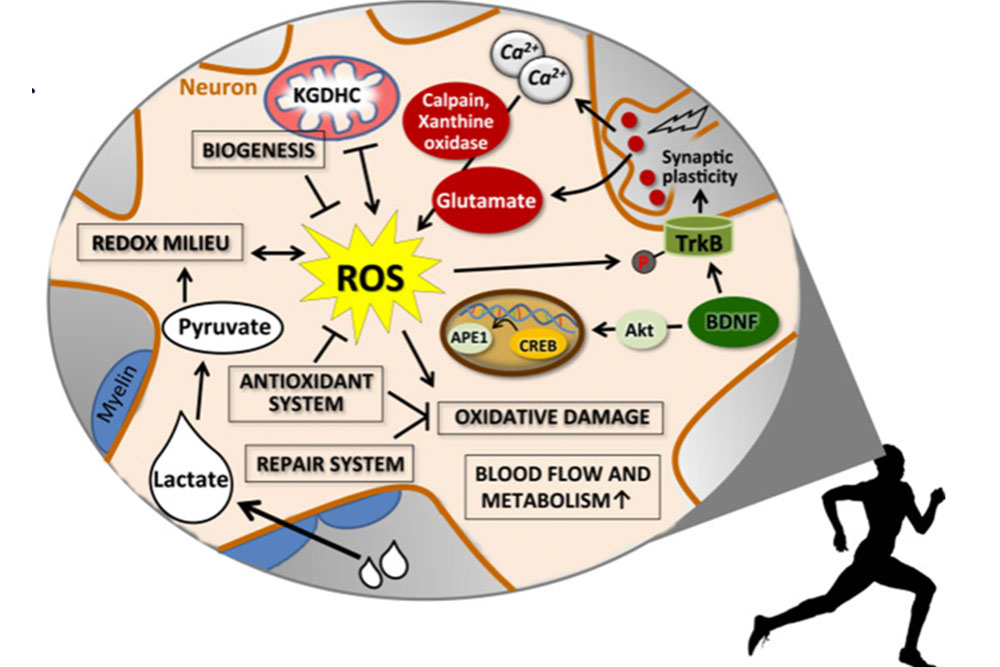

At a cellular level, aerobic exercise has been shown to increase the number and efficiency of mitochondria within your body. This alone causes vast improvements in your ability to breakdown both fats and carbohydrates for energy.

And this is important, why?

Because it can cause an improvement in metabolic flexibility, obviously.

Diurnally, regular weight training has been shown to increase the insulin sensitivity of your muscle cells. With this in mind, weight training can cause significant reductions in insulin secretion and resting blood sugar, leading to sustained improvements in cellular function.

As a result, exercise should always be one of your first points of call when it comes to improving metabolic flexibility.

You may like: The Importance of Nutrition on Brain Health

Metabolic flexibility and diet

I have spoken at length about how the American diet is absolutely terrible for metabolic flexibility. However, it is worth noting that there are certain ways of eating that you can adopt that have clear implications for your metabolic flexibility.

Ketogenic diet and metabolic flexibility:

Metabolic flexibility and the keto diet really do go hand in hand (Gershuni, 2017).

The ketogenic diet describes a way of eating that is high in fats, moderate in protein, and extremely low in carbohydrates. In short, when you adopt the keto diet, you starve your body of carbohydrates, forcing it to breakdown fats for energy.

This is super important, as it has been shown time and time again to cause huge improvements in insulin sensitivity, while also enhancing your ability to breakdown fats for energy – which is indicative of improved metabolic flexibility.

As a bonus, you don’t need to follow the ketogenic diet forever to receive these benefits. In fact, simply applying it for 4-6 weeks every 4-6 months should be enough to see sustained improvements in your metabolic flexibility.

Intermittent fasting and metabolic flexibility:

Now let’s move onto metabolic flexibility and intermittent fasting (Arnason, 2017).

Intermittent fasting describes small periods of eating that are broken up by longer periods of not eating (AKA fasting).

Some intermittent fasting diets suggest that you simply extend your overnight fast by a few hours, while others recommend you abstain from eating for days at a time – however when most people say intermittent fasting, they are talking about time-restricted feeding.

This intermittent fasting is the type that simply has you extend your overnight fast.

Like the ketogenic diet, intermittent fasting has been shown to cause marked improvements in blood sugar levels, weight management, and insulin sensitivity – and as such, has massive implications for metabolic flexibility.

It is honestly one of the most powerful dietary strategies you can employ to maximize your health quickly and efficiently.

Best ways to increase metabolic flexibility

Taking the above into consideration, I wanted to outline how to create metabolic flexibility easily and efficiently. Each of these steps is relatively simple in isolation, but as a collective can have a huge impact on your health:

- Perform 2-3 sessions of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise per week (walking, jogging, and cycling are perfect here)

- Start doing 1-2 sessions of high-intensity interval training per week

- Get in the gym 2-3 times per week and perform full-body weights training using large compound movements such as squats, deadlifts, split squats, rows, and presses

- Implement a ketogenic diet for 6 weeks, every 3-4 months

- Start an intermittent fasting protocol where you extend your overnight fast by 5-6 hours every day and stop eating after 7 pm every night.

- Cease eating heavily processed carbohydrates (even when you are not following a ketogenic diet)

Like I said – simple!

Take-Home Message

Over the last few decades, our health has declined rapidly – and a large part of this comes down to the fact that we have lost our ability to be metabolically flexible.

However, it isn’t a death sentence – in fact, using the tips outlined in this article you can improve your health take your metabolic flexibility back for good!

References

Goodpaster, Bret H., and Lauren M. Sparks. “Metabolic flexibility in health and disease.” Cell metabolism 25.5 (2017): 1027-1036.

Smith, Reuben L., et al. “Metabolic flexibility as an adaptation to energy resources and requirements in health and disease.” Endocrine reviews 39.4 (2018): 489-517.

Galgani, J., and E. Ravussin. “Energy metabolism, fuel selection and body weight regulation.” International journal of obesity 32.7 (2008): S109-S119.

Kahn, Barbara B., and Jeffrey S. Flier. “Obesity and insulin resistance.” The Journal of clinical investigation 106.4 (2000): 473-481.

Battaglia, Gina M., et al. “Effect of exercise training on metabolic flexibility in response to a high-fat diet in obese individuals.” American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism 303.12 (2012): E1440-E1445.

Gershuni, Victoria M., Stephanie L. Yan, and Valentina Medici. “Nutritional ketosis for weight management and reversal of metabolic syndrome.” Current nutrition reports 7.3 (2018): 97-106.

Arnason, Terra G., Matthew W. Bowen, and Kerry D. Mansell. “Effects of intermittent fasting on health markers in those with type 2 diabetes: A pilot study.” World journal of diabetes 8.4 (2017): 154.

Bird, Stephen R., and John A. Hawley. “Update on the effects of physical activity on insulin sensitivity in humans.” BMJ open sport & exercise medicine 2.1 (2017): e000143.

You May Like!