Is it as Simple as a Walk in the Park?

Gillian White , BSc, MSc, PhD (candidate)

Department of Exercise Sciences, University of Toronto

Is it as Simple as a Walk in the Park?

Earlier this summer, I ran a trail half marathon. I like running, but the course is challenging with 1600m vertical change so you really need to train well. Unfortunately for me, the timing of the race fell a week after my 3-week European vacation during which time my only training consisted of drinking red wine and eating croissants. Needless to say – I was not prepared. When the morning of the race came, I was in such a bad headspace that I was going to just quit before I even put my runners on but my pride prevailed and I decided to suck it up and just suffer.

As soon I set out on the first 100m of the race, my mood changed immediately! Not only was I not hating every step and thinking about how hard the race was going to be, I was genuinely enjoying myself and could feel the smile growing on my face. And that got me thinking – what is it about running through the trees that just feels so inherently good?

Behind the Research

Luckily for me, there’s a lot of research available on the benefits of nature for health and well-being. Furthermore, some of the research is downright shocking! Generally speaking, the majority of studies indicate some reduction of stress. There’s either a direct reduction in stress hormones and fight/flight activation, or downstream changes which indicate a reduction in stress. The basic principle behind this effect is that we evolved spending our time in nature. Thus, to put it crudely, our genes expect nature. The cityscapes and pavement that are commonplace to our everyday lives for most of us are a novelty to our ancient genes. Conclusively, our surroundings are incongruent with the environment in which our genes developed through centuries of evolutionary selection.

If you look around and think about it, there are lots of examples of how evolution effects our unconcious responses to things. An extreme example is the visceral feeling of danger caused by heights. Of course in some people it’s more extreme than in others, but overall, we evolved to react to the danger presented by heights with stress and fear to avoid injury/death caused by a fall. Birds, evolving to exist at heights wouldn’t experience this. Ultimately, in a state that doesn’t match how we evolved, our genes function sub-optimally or in a basal state of disarray. As a result, we get dysfunction that manifests as a breakdown of health, either mental or physical. But how does stress affect our health, and how does nature affect stress?

Related Article: Become a Runner at any Age

Stress & Health

Stress can be caused by any perceived threat to our body’s natural set point or homeostasis and can be psychological or physical. Evidence of stress activation can be categorized into three interconnecting arms of physiological stress system activation: Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) Axis activation, autonomic activation, and inflammatory activation. The HPA system is responsible for changes in stress hormones in the blood, especially cortisol. Cortisol is important for fight or flight priming of the body in times when fast fuel sources in the blood, a narrow focus of thinking, and energy diversion from immune and other systems is advantageous.

However, when it’s persistently activated the up-regulation of stress hormones is linked to illnesses including cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, obesity, osteoporosis, and depression/anxiety among others. The most significant effects of chronic up-regulation of cortisol and other stress hormones is on immune function (increasing risk of infections and cancer and impeding wound healing) and brain function (increasing risk of depression/anxiety and reducing optimal functioning of learning and memory).

Autonomic Activation

Similarly, autonomic activation is important for fight or flight. It is a result of the net balance of activation between the stimulating sympathetic nervous system and the relaxing parasympathetic nervous system. The stimulating sympathetic nervous system increases heart rate, blood pressure, alertness, and muscle tone. All of these are important in the face of an immediate stressor. However, when this activation is persistent, these systems become dysregulated. Because the three stress systems operate together, they tend to result in similar health issues. Sympathetic activation contributes more significantly to the risk of cardiovascular disease and anxiety though.

An important aspect of the way these two autonomic nervous systems operate is that they function reciprocally – so when the sympathetic system is active, the parasympathetic system is less active, and the parasympathetic system is largely responsible for deactivating the sympathetic system. In this way, the parasympathetic system’s functioning is important for taking the body out of an active stressed state and allowing it to enter a state of relaxation, restoration, and recovery.

Inflammatory System

Lastly, the inflammatory system includes mediating molecules, ‘cytokines’, necessary for activating the immune system and coordinating repair of damaged tissues. Similar to the other two stress systems, inflammation is important acutely for protecting the body in the event of physical injury; however, prolonged and persistent elevation of inflammatory mediators are deleterious to our health. Cytokines circulating in the blood are crucial signaling molecules. They are becoming an increasingly popular area of study owing to their dysregulation in a wide array of diseased states in addition to those associated directly with inflammatory processes like rheumatoid arthritis and autoimmune illnesses. Notably, risk of obesity, cancer, mental illnesses, and cardiovascular disease have been attributed to chronic inflammatory processes, as well as more insidious conditions like aging, chronic fatigue, and general sickness behaviour.

Related Article: Get Outside and Exercise – Your Immune System Will Thank You

Nature & Stress

So how does this happen? There are some direct of components found in natural environments that stimulate immune function and relaxation. Commonly cited candidates include phytoncides produced and released by plants, mycobacterium vaccae found in soil, and enhanced concentrations of negative ions in the air of regions with mountains, forests, or moving waterways (Kuo 2015). These natural phenomena confer immune boosting effects and tip the balance of autonomic activation in favour of parasympathetic stimulation and have been linked to lower risk of infectious diseases, cardiovascular health, and depression. In combination with these direct effects are the indirect effects of reducing stress activation.

As discussed above, chronically activated stress systems contribute the the development of a number of illnesses. Thus, the observation that interacting with nature reduces the activation of these systems, indicated by their biological mediators (decreased cytokines, cortisol; increased immune cells and parasympathetic activation) and improves many of the health outcomes associated with stress activation supports the idea that nature improves health by reducing stress.

Anti-Stress Hormone Creation

Anti-Stress Hormone Creation

Specifically, the many health effects of walking in nature compared to walking in urban spaces include increased anti-stress hormone dihydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and decreased pro-stress hormone cortisol (Li 2011), increased immune cells, decreased cytokines (Mao et al 2012), and decreased blood sugar (Ohtsuka 1998). Other effects that have been reported included improved sleep, increased physical activity, improved attention and brain functioning, and decreased perceptions of stress. Some of the more staggering statistics (always to be viewed with a cautious eye, but nevertheless) include a 40% cancer risk reducing change in natural killer cell activity (Imai et al 2000) and improved health outcomes equivalent to an increase in $20,000 yearly income (!!!) for people living on streets with more trees – and that’s controlling for socioeconomic status, physical activity levels, and other possible confounding factors (Kardan et al 2015).

Takeaways

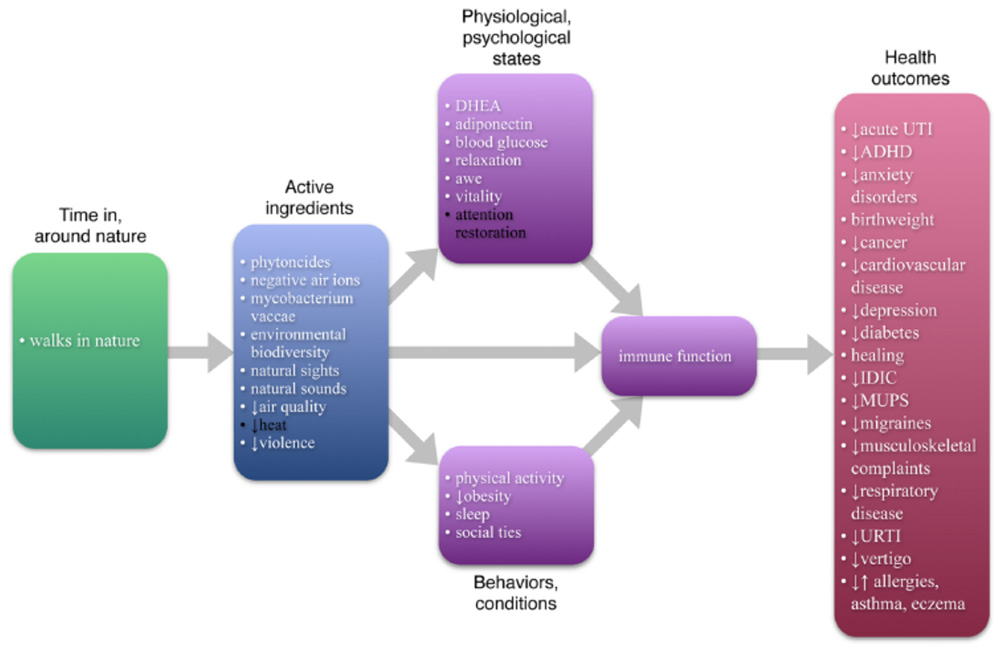

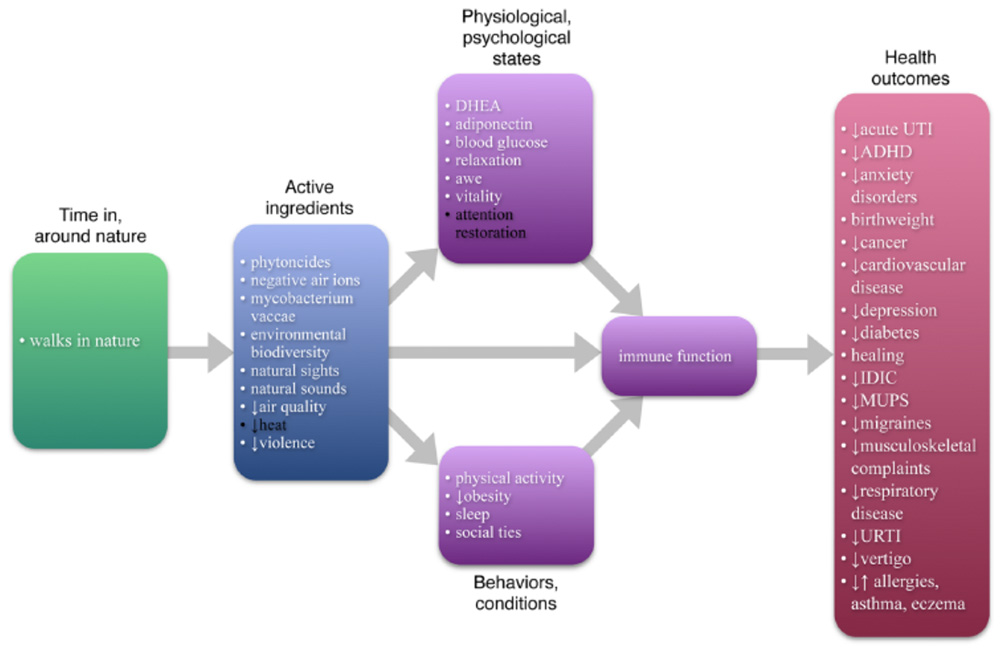

Even just seeing green space through a window or listening to sounds of nature has been shown to improve surgical outcomes (Ulrich 1984), improve brain function (Berto 2005), and restore autonomic balance (Alvarsson et al 2010). While the effects of nature are multi-faceted, a summary of the direct changes and downstream health effects was compiled by Kuo (2015) to simplify these relationships and is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1. A flow chart showing the relationships between nature and health outcomes mediated by immune functioning taken from Kuo 2015.

Overall, it seems apparent that as humans, our cells crave nature to function optimally and keep our body healthy. Whether it’s time in your local green space, planting more trees in your backyard, listening to nature sounds on your iPhone, or going for a 21 km trail run – gaining the health benefits of nature is a literal walk in the park.

References:

Alvarsson, J.J., Wiens, S., & Nilsson, M.E. (2010). Stress recovery during exposure to nature sound and environmental noise. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public

Health, 7, 1036–1046.

Berto, R. (2005). Exposure to restorative environments helps restore the attentional

capacity. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 25, 249–259.

Imai, K., Matsuyama, S., Miyake, S., Suga, K., & Nakachi, K. (2000). Natural cytotoxic activity of peripheral-blood lymphocytes and cancer incidence: an 11-year follow-up study of a general population. Lancet, 356, 1795–1799.

Kardan, O, Gozdyra, P., Misic, B, Moola, F, Palmer, L.J., Paus, T. & Berman, M.G. (2015). Neighborhood greenspace and health in a large urban center. Nature – Scientific Reports, 5, 11610.

Kuo, M. (2015). How might contact with nature promote human health? Promising mechanisms and a possible central pathway. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1093.

Li, Q., Otsuka, T., Kobayashi, M., Wakayama, Y., Inagaki, H., Katsumata, M., et al. (2011). Acute effects of walking in forest environments on cardiovascular and metabolic parameters. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 111, 2845–2853.

Ohtsuka, Y., Yabunaka, N., Takayama, S. (1998). Shinrin-yoku (forest-air bathing and walking) effectively decreases blood glucose levels in diabetic patients. International Journal of Biometeorology, 41, 125–127.

Ulrich, R.S. (1984). View through a window may influence recovery from surgery.

Science, 224, 420–421.

You Might Like: