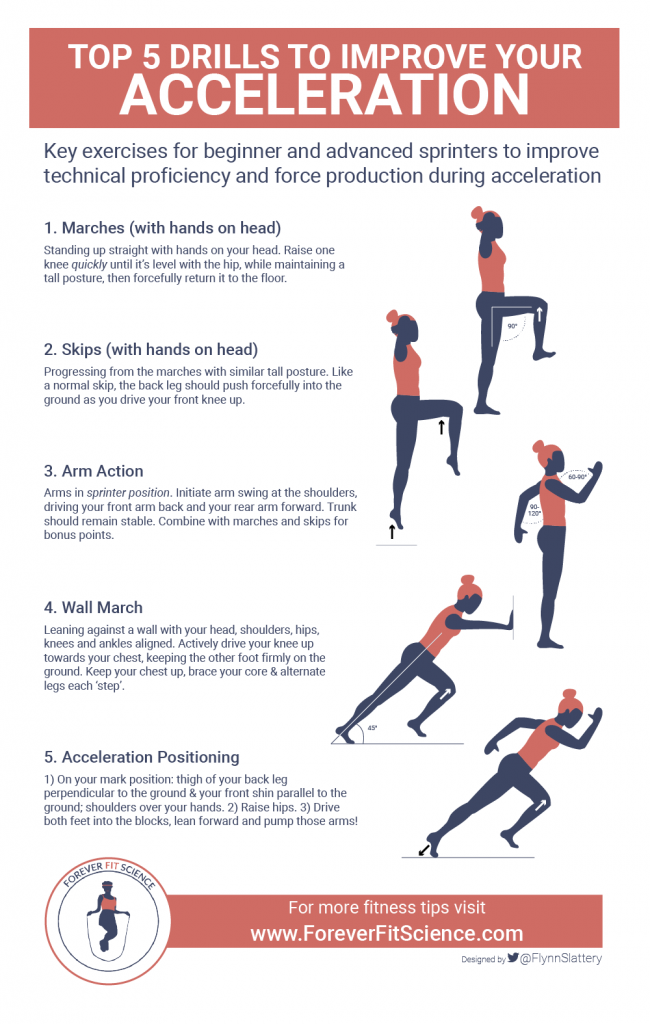

Top 5 Drills to Improve Your Acceleration

Hunter Bennett

If you took a close look at any track-based sprint event, you can begin to break it down into four key phases – the start phase, the acceleration phase, the maximal velocity phase, and a phase of deceleration.

Now, while each of these phases holds specific importance within the realm of successful track performance (with the exception of the deceleration phase, which is unfortunately unavoidable), many would agree that it is the acceleration phase that truly dictates sprinting success.

And if you take the time to think about it, it makes sense.

Acceleration essentially describes the rate at which you increase your sprint speed – and with this in mind, you can start to see why it holds so much importance.

You see, while a bad start can certainly impact the outcome of a given race, you can still recover if you can accelerate rapidly. Moreover, your likelihood of success during a given race is going to increase the longer you spend during the maximal velocity phase. Now, the greater your acceleration, the faster you can reach your maximal velocity – and therefore the more time you can spend at maximal velocity, thus improving sprint performance.

So, in short, acceleration is key.

How Can You Improve Acceleration?

If we were to look at it in a very simplistic sense, the ability to accelerate can be broken down into two components: Firstly, the amount of force that you can put into the ground each step, and secondly, how quickly you can apply that force each step (Mackala, 2015).

Although this doesn’t sound like much, it does tell us two very important things – to be able to accelerate rapidly you need to have the strength (the ability to produce force), and you need to be able to express that strength quickly and efficiently.

This also provides us with some guidance around exercise prescription – namely the fact that we can improve acceleration through two methods:

- Gym based training methods: which improve strength and other force production capabilities (Wisloff, 2004)

- Track based training methods: which improve movement efficiency and the ability to express force rapidly during sprint specific movement tasks (Morin, 2011)

Today we are going to focus on the latter of these two, being that it is arguably both the most accessible and important training modality for beginner and advanced sprinters alike.

Related Article: Training Factors to Improve Sprint Performance & Speed

The Benefits of Track Based Training for Acceleration

While sprinting may seem somewhat simple in premise, it truly is a highly technical sport. The ability to move your body through space in an efficient manner is integral to  maximizing your sprint capabilities.

maximizing your sprint capabilities.

Furthermore, your sprint technique genuinely dictates your ability to accelerate rapidly. If your technique is sound, a greater percentage of the force you produce each step is used to propel you forward, and less is wasted through inefficient movement (Morin, 2011).

In a similar sense, this modality of training also has the potential to increase your neuromuscular force production capabilities – meaning that it can further enhance the speed at which you produce force, which has obvious implications for enhancing acceleration.

Now, these improvements come from maximizing efficiency in three key areas:

Body Position During Acceleration

Your body position during the acceleration phase is considerably different from that observed at maximal velocity. During this stage, the angle of your body our body is much more horizontal. Your shins need to be more horizontal, and your trunk should form a straight line with your rear leg, creating an angle of around 45 degrees to the ground.

Rapid Force Production

As previously mentioned, acceleration is heavily dictated by your ability to apply force into the ground rapidly. During the acceleration phase, you will spend more time on the ground than you would at maximal velocity.

As such, your focus needs to be on applying as much force as you can each individual step.

With this in mind, you want to establish a triple extension at the ankle, knee, and hip, every single step. This will ensure that you produce strong, powerful strides that cover a large distance – which is imperative given that stride length has shown extremely strong associations with acceleration capacity (Mackala, 2007).

Leg Action

During acceleration, the range of motion of that your legs undergo is shortened. As a result, you want to ensure that you are determining your leg into the optimal force production position in preparation for the next step.

As a result, try and think of your legs as pistons, in which they power straight into the ground then rapidly return up into their starting position, preparing to go again.

Top 5 Drills to Improve Your Acceleration

Taking the above into consideration, there are five key exercises we can implement on the track to improve technical proficiency and force production during acceleration, causing huge improvements in performance.

These are perfect for the beginner and the advanced sprinter alike, providing the opportunity to enhance skill develop and power production simultaneously.

Marches (with hands on head)

When it comes to essential acceleration exercises, marches are king.

While this particular variation (hands on head) isn’t all that taxing, it does provide an extremely effective way of improving sprint biomechanics during the acceleration phase. With this in mind, it is best used during a warmup, prior to any high-intensity efforts to maximize technical proficiency.

During this drill, both your chin and head should be held up nice and tall and facing forward, with your hands placed on your head. The key is to drive your knee, toe up, and heel up hard every single step. As you reach the top position, the heel should recover under the butt, before you proceed to step over the knee of the grounded leg. Proceed to drive the leg down into the ground with force (landing under the hip). The ball of the foot should land before the heel.

With this movement, make sure you get the leg high and keep your chest up tall. Common mistakes include slumping forward and losing head position.

Remember, in the top position, the hip should reach 90 degrees of flexion (the top of the thigh parallel to the ground), and the rear leg should be fully extended, creating a straight line from the foot to the top of the head.

Skips (with hands on head)

Think of this next variation as a progression of the marches above. Similar in premise, this great exercise further reinforces efficient acceleration movement mechanics while also enhancing force production.

Start with your head and chest up tall, with your hands placed gently on your head. Commence the movement as you would a normal skip, with the grounded leg driving into the ground with force.

Your hip, knee, and ankle should undergo triple extension to push you off the ground. During this movement, actively drive your opposite leg up. Land on the same leg you first skipped off, before alternating and driving the opposite leg into the ground, repeating the process.

During this movement do not lose chest and head position and remember to actively drive the on-grounded leg into the air – your hip should be flexed to 90 degrees in the top position. Like the march, your grounded leg should finish completely extended, forming a straight line from your foot to the top of your head.

Related Article: How to Achieve a Near Perfect Sprinting Technique

Arm Action

Often overlooked, the arms actually play an incredibly important role in sprint and acceleration performance. During sprinting, the arms help transfer force through the torso and into the hips. With this in mind, improving your arm action is essential to optimizing this force transfer.

This simple drill teaches this effective transfer.

Start with your arms in sprint position (one arm forward, and one arm back). Your front arm angle should be between 60 and 90 degrees at the elbow, with your rear arm being  between 90 and 120 degrees. Initiate arm swing at the shoulders, driving your front arm back and your rear arm forward. The arm coming forward should finish around cheek height, while the rear arm should pass the hip.

between 90 and 120 degrees. Initiate arm swing at the shoulders, driving your front arm back and your rear arm forward. The arm coming forward should finish around cheek height, while the rear arm should pass the hip.

During this movement, your trunk should remain still and stable, and your arms should move in a straight line – they should not pass the midline of the body.

While this variant is extremely simple, over time it can be combined with both the marches and skips mentioned above as means of progression.

Wall March

Our next drill further reinforces proper acceleration technique, while also allow providing an opportunity to develop the horizontal force production capacities that are integral to the acceleration phase of sprinting.

Start with your hands flat against a wall in front of you. Your head, shoulders, hips, knees, and ankles should be aligned, with your body at a 45-degree angle to the ground. Actively drive your knee up towards your chest, while keeping the other foot firmly planted on the ground. Alternate legs each ‘step’.

Your thighs should finish parallel to the ground and perpendicular to your torso – this is essential to learning proper knee drive during sprinting. If your knee drive is not high enough, your steps will be short, inefficient, and lacking power.

During this movement, your front shin should be at the same angle as your rear shin (45 degrees) and your foot should remain dorsiflexed. Throughout the entire movement, the grounded leg should remain fully extended, forming a straight line from the ground to the top of the head.

Acceleration Positioning

And finally, when it comes to initiating the acceleration phase of a sprint, your start position is essential. Ensuring that your start position is sound means that you can enter the acceleration phase as quickly as possible while maximizing your force production out of the start position.

During the initial start position (on your mark) the thigh of your back leg should run completely perpendicular to the ground, while your front shin should be parallel to the ground. Your arms should be straight and held slightly wider than shoulder-width, with your shoulder sitting just in front of your hands. Your head and neck should be held neutral, and your eyes focused on the ground. During this position, your fingers should be spread, forming a bridge between your thumb and fingers.

Once you hear the words ‘on your mark’ its time to begin the transition. Your hips should rise slowly, while your shoulder remains still. During this movement, you need to push your entire foot back against the block. The knee of your front leg should be angled around 90-100 degrees, with your rear leg around 120-135 degrees. Your eyes should remain looking at the ground.

And the gun goes off.

As soon as you hear this noise, drive both of your feet into the blocks at the same time, exploding out as far as possible. Your rear leg should reach triple extension at the ankle, knee, and hip, and your entire body should be angled at 45 degrees (and leaning forward). Aggressively drive your knees up and pump your arms. Keep your eyes focused about 5 meters in front of you.

Putting it Together

Now, the first four exercises on this list can be performed sequentially as part of a warm-up prior to a sprint session. As they each build upon one another, they provide the perfect way to enhance sprint technique and performance prior to moving into some actual sprint training.

And as a bonus, as they are not particularly taxing, they can be performed regularly and with a fairly high volume (think 3 sets of 15 per side).

The final drill should be practiced efficiently every single sprint that you do during training. This will ensure that your start becomes second nature, and your acceleration phase is maximized every single time.

Take Home Message

The acceleration phase is arguably the most important aspect of sprint performance, ensuring that you can get to maximal velocity as fast as possible. The five exercises in this list teach the foundations of efficient acceleration, making them absolutely perfect for the beginner and advanced sprint athlete alike.

References

Maćkała, Krzysztof, Marek Fostiak, and Kacper Kowalski. “Selected determinants of acceleration in the 100m sprint.” Journal of human kinetics 45.1 (2015): 135-148.

Wisløff, U., et al. “Strong correlation of maximal squat strength with sprint performance and vertical jump height in elite soccer players.” British journal of sports medicine 38.3 (2004): 285-288.

Morin, Jean-Benoît, Pascal Edouard, and Pierre Samozino. “Technical ability of force application as a determinant factor of sprint performance.” Medicine and science in sports and exercise 43.9 (2011): 1680-1688.

Mackala K. Optimisation of performance through kinematic analysis of the different phases of the 100 meters. New Studies in Athletics 22.2 (2007):7–16

JOIN OUR NEWSLETTER

You Might Like: