Resisted Sprinting For Speed & Acceleration Development

Hunter Bennett

Over the last decade, we have seen the world of athlete development come along in leaps and bounds (both literally and figuratively).

We have seen the widespread uptake of strength training, plyometrics, and movement specific exercise. They are prevalent in practically every sport on the planet. All have been used with great success to cause vast improvements in physical performance.

But why stop there?

Every single week new training methods are being implemented to further improve performance. They are an effective addition to the already established training methods discussed briefly above.

And one such training method that has gained some serious traction in athlete development circles is resisted sprinting.

What is resisted sprinting?

Resisted sprinting is very much what it sounds like – a unique training method that consists of performing high intensity sprinting exercises with the addition of load or resistance to promote further adaptation (Gil, 2018).

In this scenario, load is often applied through one of three means:

- The addition of weight through the use of a sled

- Banded resistance anchored posteriorly

- An increase in air resistance through the use of a parachute

Each of these methods essentially acts to overload the body in the same manner. They add resistance to the sprinting movement, meaning that the individual needs to produce more force to move through space.

Related Article: Are Thermogenic Dietary Supplements Safe & Effective For Resistance Training?

What are the benefits of resisted sprinting?

Now, as I am sure you can imagine, adding load to sprints offers quite a unique training stimulus that cannot be obtained through any other means.

Sprinting alone has been shown to act as a potent method of improving speed and acceleration in untrained individuals. However, over time (and as the individual becomes more physically apt), further stimulus is required to drive further adaptation.

Which is where resisted sprinting enters the equation (Petrakos, 2016; Cross, 2018).

By overloading the sprint movement, resisted sprinting essentially increases the amount of force required to both accelerate away from a stationary position and maintain maximal sprinting speed.

With this in mind, the addition of resisted sprinting into a training routine has been shown to consistently cause significant improvements in both acceleration and maximal velocity.

What sports is resisted sprinting good for?

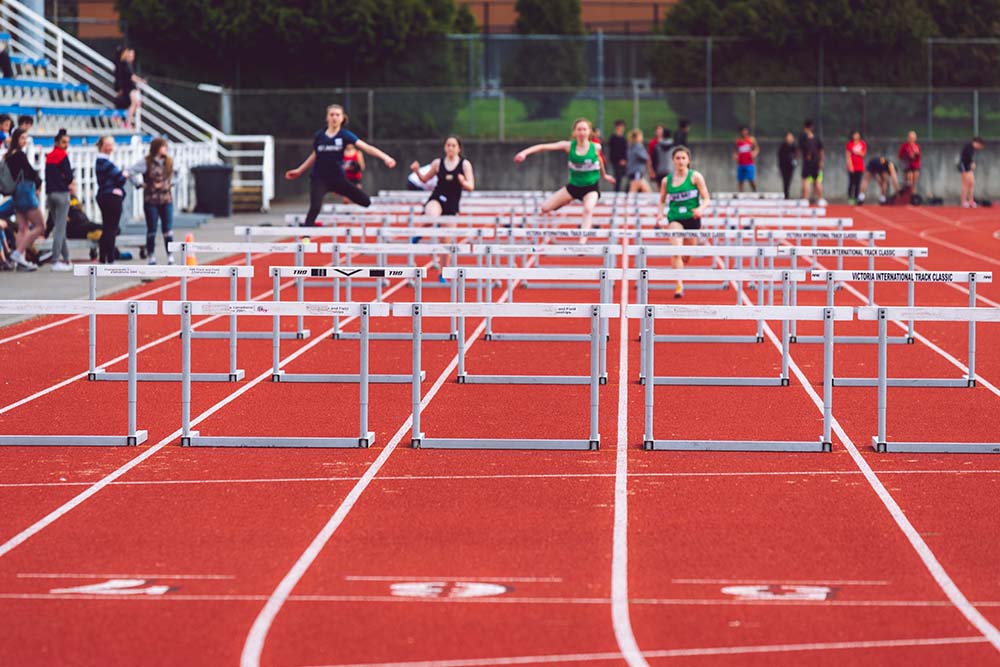

There is a saying in athletic performance circles that ‘speed kills’ – which I think holds true in practically every track and field sport on the planet.

Basketballers, footballers, baseballers, sprinters, and even endurance athletes have a need to get faster in some capacity, to maximize their performance. As a result, resisted sprint training is a useful training method that can be used by any and every athlete to enhance performance.

If your goal is to get faster, then there is really no reason not to be doing it.

The best resisted sprinting exercises

So, you now know that resisted sprinting offers a powerful method of improving performance – as such, it is time to talk about how you can best implement into your training.

As I alluded to above, there are three main methods we can use to overload the sprinting movement, which gives us some insight into our three best resisted sprinting exercises.

- Sled resisted sprints

- Band resisted sprints

- Parachute resisted sprints

Within this section, we have also outlined what we believe to be resistance sprinting equipment on the market at the moment.

So, without further ado!

Sled resisted sprints

Sled resisted sprints describe a modality of resisted sprinting where a sled is attached to the body via a harness, and then dragged behind the body during sprinting repetitions.

This is commonly accepted to be one of the most effective methods of implementing resisted sprint training. It has consistently shown a positive training effect within the literature. Moreover, it can easily be progressed by adding more load to the sled. Additionally, it does not require a training partner to be completed effectively.

At this point in time, most of the research supports using lighter loads attached to the sled, as not to disrupt sprinting mechanics.

Often 6-8 sprints per session (for 2-3 sessions per week) with 2-3 minutes between sprints is optimal here. Sprint distances from 10 – 50 meters can be implemented successfully, although we recommend starting on the shorter end of the spectrum, and then gradually progressing in distance.

Band resisted sprints

Band resisted sprints describe a specific mode of resisted sprint training. An elastic band is attached at the waist and then held by a training partner directly behind you. During the sprinting movement, your training partner gradually reduces the tension in the band, until maximal velocity is achieved.

Much like sled resisted sprints, this offers an acceptable way of adding load to the sprinting movement, however it is much less precise as the load is dictated by the individual applying the resistance.

Again, 6-8 sprints per session (for 2-3 sessions per week) with 2-3 minutes between sprints is optimal here, and sprint distances from 20 – 50 meters can be implemented successfully.

Parachute resisted sprints

Last but not least we have parachute resisted sprinting.

This form of resisted sprint training is quite simple in premise. You simply attach a parachute to the back of a belt before commencing a sprint. Then, as you take off, the parachute fills with air and provides resistance.

This offers a useful and affordable method of training that can be implemented by yourself. Like the band resisted training, it is less precise than the sled resisted training as you cannot specify the exact load – however, it has still been proven an effective option (Paulson, 2011).

Similarly, we recommend 6-8 sprints per session (for 2-3 sessions per week) with 2-3 minutes between sprints, and sprint distances from 10 – 50 meters.

The other best sprinting acceleration exercises

Resisted sprinting is a great tool you can use to improve acceleration. It is certainly not the only tool you can use.

You see, resisted sprinting is very specific to the act of accelerating. In this manner, it would be deemed to have a high degree of specificity, because it replicates the movement we are trying to improve.

As a result, we have an opportunity to further improve acceleration by focusing on developing the physical qualities that underpin acceleration performance. Above all this includes lower body strength and lower body power (Mackala, 2015).

From an acceleration perspective, this means both increasing the amount of force that you can put into the ground each step (strength) and improving the speed at which you can apply the force of each step (power) (Wisloff, 2004).

Which is exactly where gym-based training comes into contention.

When stepping into the gym for the sole purpose of improving speed and acceleration, you want to opt for exercises that replicate the joint demands of sprinting. Additionally, you want to place a premium on the posterior chain.

With this in mind, my go-to exercises for strength development are:

And my favorite exercises for power development are:

- Box Jumps

- Power Cleans

If you want some more information around how you can best implement these exercises into your training to maximize acceleration, I have actually written a very detailed article on the topic: 5 Best Gym Exercises to Improve Acceleration.

Take Home Message

Every week a new training gimmick appears, suggested to improve performance and make you a better athlete. While many of these methods don’t hold up to the hype, resisted sprinting certainly does.

By forcing an increase in force production during sprinting, resisted sprint training offers an extremely effective means of increasing acceleration and maximal velocity. It’s a ‘must have’ in any athletes training program!

References

Gil, Saulo, et al. “Effects of resisted sprint training on sprinting ability and change of direction speed in professional soccer players.”. Journal of sports sciences 36.17 (2018): 1923-1929.

Petrakos, George, Jean-Benoit Morin, and Brendan Egan. “Resisted sled sprint training to improve sprint performance: A systematic review.”. Sports medicine 46.3 (2016): 381-400.

Cross, Matt R., et al. “Training at maximal power in resisted sprinting: Optimal load determination methodology and pilot results in team sport athletes.”. PloS one 13.4 (2018): e0195477.

Paulson, Sally, and William A. Braun. “The influence of parachute-resisted sprinting on running mechanics in collegiate track athletes.” The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 25.6 (2011): 1680-1685.

Maćkała, Krzysztof, Marek Fostiak, and Kacper Kowalski. “Selected determinants of acceleration in the 100m sprint.” Journal of human kinetics 45.1 (2015): 135-148.

Wisløff, U., et al. “Strong correlation of maximal squat strength with sprint performance and vertical jump height in elite soccer players.”. British journal of sports medicine 38.3 (2004): 285-288.