Does Sprint Performance Decline With Age?

Exercising regularly across your lifespan is the perfect way to maintain health and function well into your golden years – and one of the best modes of exercise on the planet is unquestionably sprinting.

Sprinting provides a unique combination of strength, power, balance, and coordination into one single exercise, making it incredibly effective.

But did you know that how you sprint can change significantly as you get older? More importantly, did you know that this impacts what exercises you need to be doing to improve your sprint performance?

Well it does – which is exactly what we wanted to outline in this article.

Increasing life expectancies but declining activity levels

The reason I have spent a bit of time talking about maintaining function across the lifespan comes down to the fact that we (as a global population) are getting older.

The reason I have spent a bit of time talking about maintaining function across the lifespan comes down to the fact that we (as a global population) are getting older.

Whether it’s due to improved healthcare, advances in medication, or simply the fact that we are now living less stressful lives, we cannot be sure – but this doesn’t really matter.

What matters is that we are an aging population.

Now, this is a concern because although we are indeed living longer, we are not actually seeing an increase in healthy life years. We are reaching an age where both our function and health declines, after which we need to rely on medications and aids to keep us going.

Not good…

And the reason for this?

Physical inactivity.

Yep, a simple lack of exercise.

See, exercise is arguably the most effective method of maintaining health and function. It staves off cardiovascular disease, diabetes, osteoporosis, sarcopenia, and even dementia – all while simultaneously increasing your quality of life.

In short, it keeps you functioning well into your golden years.

But for some reason, physical activity continues to decline with age – which is the main driver for this loss of healthy years (Takagi, 2015).

Related Article: Fitness Helps Brain Function As We Age

Why do we become inactive as we get older?

You might be wondering why we become less active as we age – and as I am sure you can imagine, there are several different reasons.

First and foremost, as we age, we tend to transition into more sedentary jobs. Whether it be shifting into a management position, or making a complete career change, as we get older, we move into jobs that require more sitting, and less manual labor.

We also start families, which equates to both a change in priorities, and less leisure time – which simply means less time for physical activity.

Finally, these early changes in activity levels result in a decline in fitness, and an associated decline in muscle strength and muscle function. While minimal, these small declines make it more challenging for you to undertake exercise – which results in the avoidance of exercise.

Over time, this can become a huge driver for further inactivity, which can itself create a very vicious cycle of deconditioning.

Masters Athletes

However, one group that continues to buck the trend of reduced activity levels are master’s athletes. For whatever reason, they continue to push their body to its limits, exercising well into their golden years, and keeping their ability to function as a result.

But, as I am sure you can imagine, there are some risks associated with being competing in masters athletics – although they may not be as severe as you think.

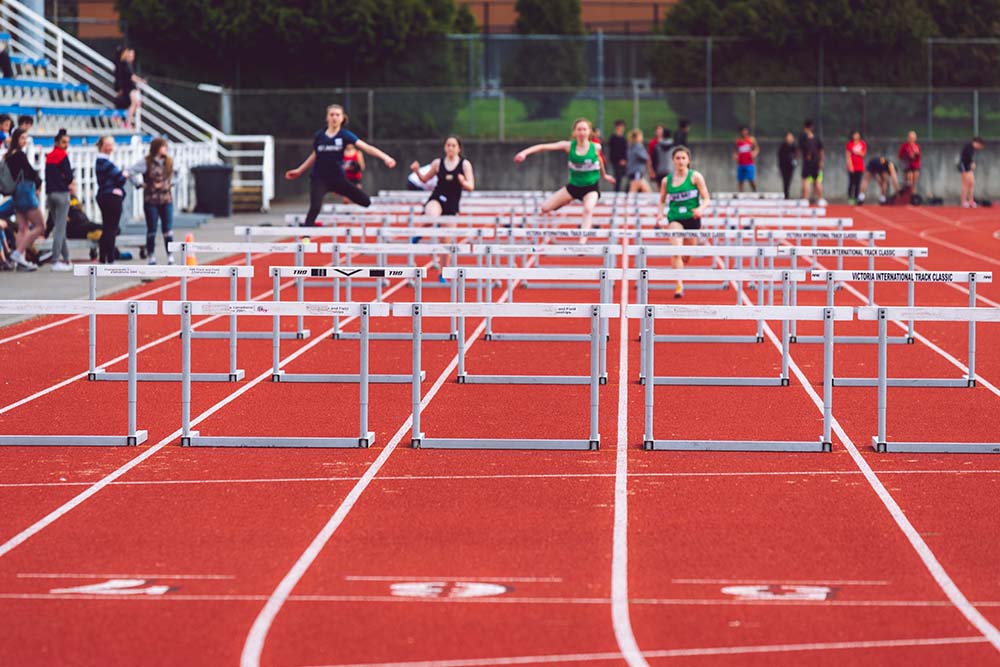

With this in mind, it is important to note that we will be talking predominantly about track events moving forward (rather than both track and field events), as these are the most common masters events.

Moreover, they relate directly to sprinting, which I have already stated is one of the best ways to keep functioning well as our life expectancy increases.

Injury risk in master athletes

There is a common misconception within the health industry at large that injury rates in athletic populations increase with age – but this isn’t the case at all.

In fact, there is a large body of evidence clearly demonstrating that the injury rates of master athletes are very similar to those of younger athletes who compete within the exact same sport (Baker, 2015).

However, they do appear to be at an increased risk of specific types of injuries.

Namely, lower limb injuries (Ganse, 2014).

There is some research to suggest that masters athletes may be at a higher risk of hamstring and thigh muscle strains, Achilles tendon issues, calf muscle strains, and foot issues.

More importantly, this injury risk appears to increase if you are female, or if you compete in sprint events, rather than longer duration endurance events.

But why is this the case?

What are sprint kinematics?

To determine why older female sprinters are at an increased risk of injury, we are going to look at how sprint kinematics change with gender and with age – and to do so, we are first going to describe what sprint kinematics are.

Kinematics describe a branch of biomechanics that investigate the motion of objects, albeit without any concern for the forces which cause that motion.

So, regarding sprint kinematics specifically, we are talking about how the limbs and joints of the body move during sprinting.

Makes sense?

It is this analysis that gives us insight into how force is distributed throughout the body during sprinting. This is obviously of interest when we want to look at injury mechanisms – which is exactly what we are doing here today.

Influence of age on sprint kinematics

Age tends to cause some significant alterations in sprint kinematics (Dahl, 2019).

Firstly, as you get older, you are likely to experience a significant reduction in leg stiffness angle, which indicates more knee bend upon each individual ground contact. This suggests that as you age, you see a reduction in muscular stiffness, which can increase the load distributed through the passive structures of the foot.

This can have implications for foot injuries.

Secondly, you also see an increase in what is known as brake angle.

Brake angle describes the angle between your front leg during contact phase (drawn from the hip), and a line coming perpendicular to the ground. In short, this angle indicates how heavily your front foot contacts the ground.

Subsequently, this increase in brake angle again suggest that more load is distributed through the joint structures of the lower limb, rather than the muscular system.

Thirdly, with age you can also expect to see a decline in propulsion angle, which indicates a reduction in stride length. This may also suggest that as you get older, you lose a bit of push of strength, which can have implications for performance.

Lastly, there is also an age-related increase in hip flexion angle – which essentially indicates an inability to lift your knee higher during the flight phase of sprinting.

While this may not have any implications for ground contact time, it does have some implications for performance, as it indicates a loss of hip mobility – which is not good.

Related Article: Improve Performance With Mobility Training

Influence of sex on sprint kinematics

Interestingly, the differences between men and women during sprinting are relatively minimal – with the exception of one key difference.

Women see a markedly greater increase in hip flexion angle as they get older.

This indicates that females may experience a larger loss of strength as they age, which creates an inability to stride out and keep their knees high during flight phase. In turn, this may create a more severe heel strike upon landing, which can result in the onset of a foot injury – a key type of injury that women sprinters are more susceptible to at any age.

Why does sprint performance decline with age?

With all this in mind, it is important to reiterate that with these changes in sprint kinematics, sprint performance also declines with age.

But why is this the case?

Well, arguably the largest reason is related to a loss of muscle strength and stiffness (Goldspink, 2012).

As we get older, we tend to see a decline in muscle mass. This obviously corresponds with an associated decline in strength and power – both of which are essential to the maintenance of sprint performance.

It is these qualities that allow you to produce force during push off. It is also these properties that keep your lower limb muscles stiff on impact, which enhances acceleration every single time your foot contacts the ground.

Additionally, as you age, you also see a decline in hip mobility (Stathokostas, 2013).

This loss of mobility can impact your ability to lift your leg high during flight phase (think about that hip flexion angle), as well as impair your ability to stride out at maximal velocity.

Both of these factors can increase the load distributed through your joints, and lower the load distributed through your muscular system – which can further cause declines in performance.

Best exercises for masters sprinters

Taking the above into consideration, I wanted to give you some great exercises that you can implement into your routine to preserve strength, power, and hip mobility well into your golden years.

Not only will this help you improve function, but will also have some huge implication for sprint performance.

So, without further ado, I give you the best exercises for masters athletes!

- Half Kneeling Couch Stretch

The half kneeling couch stretch is the perfect way to target the hip flexor muscle group and rectus femoris muscle. These muscles often become short and stiff, which can limit your ability to stride out each step.

In a kneeling position, start the stretch by backing both of your feet up against a wall, or against the upper cushion of your couch (hence the names, ‘couch stretch’). Then proceed to slide one of your legs backwards so that your knee fits into the corner where the floor or couch meets the wall.

In this position, your shin should be as close to the wall as you can get it, and your toe should be pointed upwards. You should be in a half kneeling position, with your chest up nice and tall.

From here, squeeze the glute of your back leg as hard as you can to create a serious stretch!

- Pigeon Stretch

Much like your hip flexors, the external rotators found within your hip can also become extremely short and stiff. This can restrict movement at the hip joint, which can cause an increase in hip flexion angle.

Which is exactly where the pigeon stretch enters the equation.

Start in a normal push up position, and then bring one of your legs forward, placing your ankle just behind your opposite hand. The knee of that same leg should be sitting just behind your wrist on the same side. In this position, the outside of your knee should be pushed firmly into the ground.

Your shin should be as close to horizontal as possible.

Slowly sink down into your hips, keeping your chest up tall. Stay here for 10 deep breaths, trying to sink further into the stretch each full exhalation.

- Box Jump

Box jumps are a fantastic exercise that train muscular power. This same exercise also helps enhance muscular stiffness, which is integral to sprint performance as you get older.

Box jumps are a fantastic exercise that train muscular power. This same exercise also helps enhance muscular stiffness, which is integral to sprint performance as you get older.

Start by standing in front of the box in an athletic position. Your feet should be set a shoulders width apart, and you should be a comfortable distance from the box. When you are ready to commence the jump, rapidly descend into a quarter squat while swinging your arms downward. From this bottom position, rapidly jump up onto the box, ensuring that you fully extend your hips and swing your arms upwards.

Make sure that you land on top of the box gently.

The key here is to be soft on the landing – envision the way a cat lands on the ground.

One thing I want to reiterate is that it doesn’t matter how tall the box is – the goal here is to jump as high as you possibly can.

This isn’t going to change as the box gets higher.

- Front Squat

The front squat is a great exercise that closely replicates the torso and hip position during sprinting – making it the perfect way to build strength for sprint performance.

This movement is performed with the bar held in the ‘front rack’ position.

With this in mind, the bar should be resting on your shoulders, with your fingers under the bar (just wider than your shoulders). Your chest and elbows should be up tall throughout the duration of the movement.

Start with your feet just wider than shoulder width, and your toes pointed out slightly. Proceed to descend into a squat by dropping straight down between your heels. Keep your chest and elbows up tall the whole time.

Control the descent and reach the bottom position (the top of your thighs should be parallel to the ground) in a smooth manner. From here, proceed to drive your feet into the ground and come up as fast as you can, returning to the starting position.

Boom – that’s one rep!

- Bulgarian Split Squat

Last but not least, we have the Bulgarian split squat.

This great exercise (also known as the rear foot elevated split squat) is a single leg squatting exercise where the rear foot remains supported. This means that it both replicates the demands of sprinting closely and allows you to improve hip stability through the full range of motion used during sprinting.

This has significant benefit for strength development, while also helping you improve your sprint mechanics.

Talk about bang-for-your-buck!

Start by standing approximately 1-2 feet away from the bench behind you, while holding onto two dumbbells. Slowly reach one leg back behind you and rest the top of your foot gently on the bench.

This is your starting position.

From here, gradually descend under control until your back knee lightly touches the ground. Make sure to keep your torso neutral, and your hip flexed slightly in the bottom position. Finish the movement by pushing your grounded leg into the floor, driving back up into the starting position as explosively as possible.

During this movement you should feel a bit of stretch on your back leg – which is great!

This means that you will also see a small improvement in hip mobility, which as I mentioned above, is terribly important for your sprint performance.

Related Article: The Biomechanics of Sprinting

Putting it all together

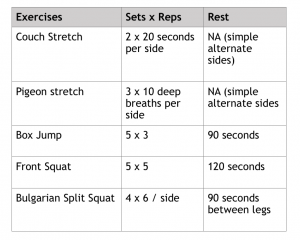

Lastly, I wanted to put all of this together into a little program that you can perform 2-3 times per week. This will improve mobility, strength, and power – all contributing the improvement and maintenance of sprint performance across the lifespan.

Take Home Message

Sprinting offers one of the most effective ways of keeping function high across the lifespan. And with the ability to simultaneously improve strength, power, and coordination, it should come as no surprise.

However, it is important to note that as you get older, you are going to experience some declines in sprinting mechanics – many of which contribute to a loss of performance a subtle increase in injury risk.

But this is not a death sentence.

In fact, you can implement certain exercises to keep your sprint mechanics on point and your performance high. So, what are you waiting for – give them a go today, and let us know what you think!

References

Baker, J. R. (2015). The prevalence and risks of injury for masters athletes: current findings (Doctoral dissertation).

Ganse, B., Degens, H., Drey, M., Korhonen, M. T., McPhee, J., Müller, K. & Rittweger, J. (2014). Impact of age, performance and athletic event on injury rates in master athletics-first results from an ongoing prospective study. Journal of Musculoskeletal and Neuronal Interactions, 14.

Dahl, J., Degens, H., Hildebrand, F., & Ganse, B. (2019). Age-related changes of sprint kinematics. Frontiers in Physiology, 10.

Goldspink, G. (2012). Age-related loss of muscle mass and strength. Journal of aging research, 2012.

Stathokostas, L., McDonald, M. W., Little, R., & Paterson, D. H. (2013). Flexibility of older adults aged 55–86 years and the influence of physical activity. Journal of aging research, 2013.

Takagi, D., Nishida, Y., & Fujita, D. (2015). Age-associated changes in the level of physical activity in elderly adults. Journal of physical therapy science, 27(12), 3685-3687.

You Might Like: