The Biomechanics of Sprinting

Alyssa Biawolas

Understanding the biomechanics of sprint running form is essential to successful sprint performance. Biomechanical variables influencing sprinting include reaction time, technique, force production, neural factors, and muscle structure. The electrical activity produced by skeletal muscles also influences sprinting. Thomas (2017) found that maximal running speeds in sprint events are achieved by creating a high force output, which means creating a high vertical ground reaction force over short contact times. Type II muscle fibers in the leg muscles and a heavy reliance on anaerobic metabolism also contribute to max running speeds.

Reaction Time

An athlete’s ability to react to the sound of the starter’s gun and push their feet and legs from the starting block, is essential to a sprint performance. This is the time from hearing “go” until the onset of electrical activity and then force production by the muscle. The faster this electrical activity begins in every muscle, the better the neuromuscular performance contributing to overall performance.

Reaction time is highly genetic but can typically improve, as it is derived from stimulation and adrenaline. Mental training and focus, as well as overspeed training, have resulted in reaction time improvements in some athletes.

Force Production

The production of force varies by muscle and the time in which that muscle is activated within the duration of your sprint. For example, your gluteus maximus reaches peak power output and electrical activity within the first 100 milliseconds at the start phase and decreases in activity throughout the rest of the sprint.

The joint and muscle activity occurring in your leg during the start of a sprint show improved performance enhancement of elite sprinters compared with beginners. Elite sprinters exert greater force production at the start of their race as compared to less skilled sprinters.

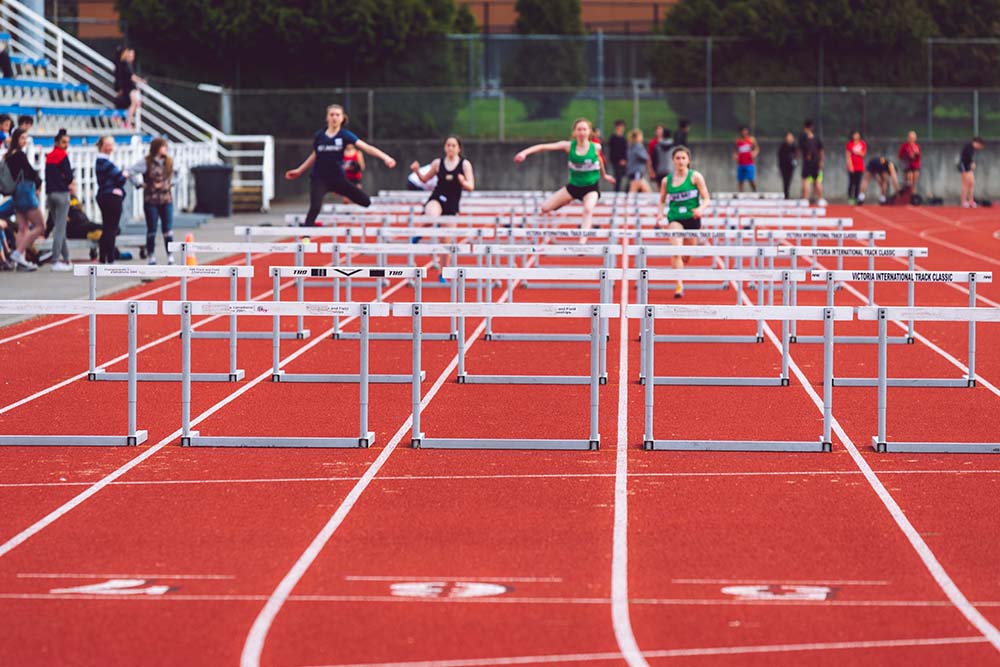

Technique

Technique is a sprinter’s ability to accelerate by increasing stride length and stride rate after the initial start phase of a race. High muscle electric activity during the acceleration phase implies that a sprinter may reach their maximum neural activity during the acceleration phase, and subsequently declines.

A sprint run requires a complex sequence of continued muscle activation through the entire body, and a sprinter’s ability to perfect their technique through training will enhance performance.

Neural Factors

The central nervous system regulates muscle force by changing the number of available motor units. Additionally, the motoneuron firing rates impact force production. This is where we get into slow (type I) and fast (type II) muscle fibers and motor units, relating to their contraction time and fatigue resistance. The force for contraction on muscle fibers during a sprint occurs over a very short period. Continued sprint training will increase your fast twitch fibers, enhancing performance.

Related Article: Agility & Weightlifting for Sprinters

Environmental Factors

A sprinter eventually reaches the constant phase of their sprint in which you’re not beginning to incline, accelerate, or decline in speed at the end of the race. A sprinter can reach their supramaximal speed due to factors such as tailwind or sprinting on a downhill.

You Might Like:

The Biomechanics of Breathing During Sprinting

Sprinting is one of the most physically demanding tasks that the human body can perform. It requires an incredible amount of explosive power, tissue resilience, and motor coordination, in conjunction with a vast body of...The Biomechanics of the Sprint Start

A perfect sprint performance is dictated by several factors, including muscle strength, explosive muscle power, a high degree of neural coordination, and most importantly – optimal sprinting technique. However, while most sprinters tend to take...How Do Sports Injury Rates Change As You Age?

As you get older, exercise becomes the most beneficial thing you can do for your body. It staves off disease and illness, all whilst helping you maintain (and often improve) joint, bone, and muscle health....Does Sprint Performance Decline With Age?

Exercising regularly across your lifespan is the perfect way to maintain health and function well into your golden years – and one of the best modes of exercise on the planet is unquestionably sprinting. Sprinting...Resisted Sprinting For Speed & Acceleration Development

Hunter Bennett Over the last decade, we have seen the world of athlete development come along in leaps and bounds (both literally and figuratively). We have seen the widespread uptake of strength training, plyometrics, and...Start Positions for Sprinters

Hunter Bennett Sprinting is one of the most incredible acts of human performance on the planet. While at first glance it may seem like quite a simple task (just run as fast as you can,...References:

Thompson, M.A. (2017). Physiological and Biomechanical Mechanisms of Distance

Specific Human Running Performance.” Integrative and Comparative Biology, 57, 2, 293–300.