4 Stages of Core Training for Lower Back Pain

Ryan Cross, B.A. Hons (Kin), MScPT, FCAMPT

Registered Physiotherapist at CBI Physiotherapy and Rehabilitation Centre in Sarnia, Ontario, Canada

Low back pain is one of the most common ailments that force people to seek medical attention. Over 80% of people will encounter low back pain at some point in their life (Cassidy et al. 1997).

Think about when you spend a weekend spring cleaning, raking leaves, or shoveling the driveway in the winter. Many people will feel soreness after some of these activities.

In most cases, low back pain resolves on its own if you keep moving. Unfortunately, sometimes low back pain can linger. When you don’t get back to normal within a few days, it is important to see your doctor or physical therapist to determine the cause of your pain and direct a treatment plan.

Recover faster from workouts with the combination of cold therapy and massage made possible by the Recoup Fitness Roller.

Recover faster from workouts with the combination of cold therapy and massage made possible by the Recoup Fitness Roller.

The cause of low back pain is multifactorial and the treatment for low back pain is multimodal, therefore seeing a professional can get you back in the game. Although not all back pain is attributable to a core weakness, it can influence symptoms and training the core can assist in recovery.

It is important to understand what makes up the “core,” when it might be implicated in low back pain, and how you can effectively train the core.

Core Concepts

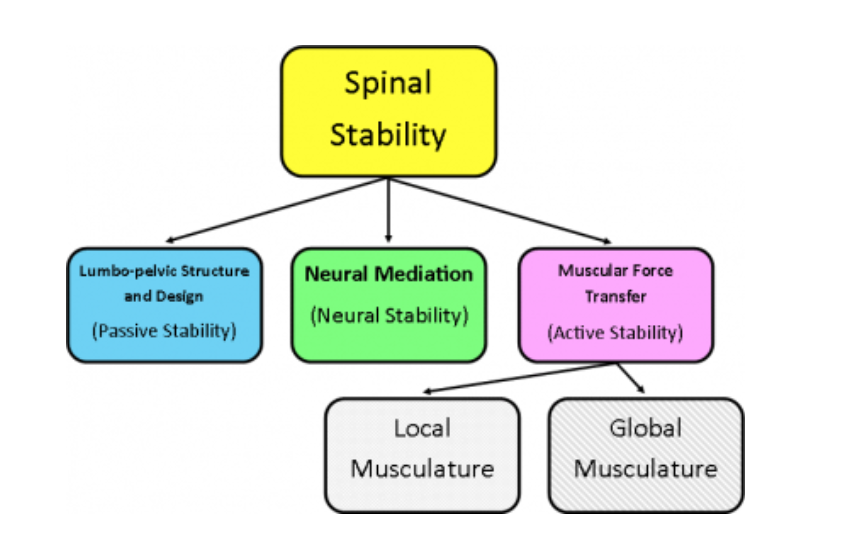

Any discussion on core training and spinal stabilization should include Panjabi’s model of spinal stability (Panjabi, 1992).

This model involves 3 interdependent systems that work together to maintain control of spinal movement. The passive subsystem comprises the static tissues, including vertebrae, intervertebral discs, ligaments, and joint capsules. The function of this system is to maintain the structure of the spine by creating tensile force during movements toward end range, transfer load between areas of the spine and body, and to transmit information to the neural system through mechanoreceptors (Huxel Bliven et al, 2013). The active subsystem consists of the core musculature, both inner and outer units. The inner unit is local to the spine and the outer unit produces global movements. These muscles provide dynamic stabilization to the spine and body, while also providing information to the neural system during movements. The neural control system is made up of the brain and spinal cord where information is transmitted in and out to determine the timing, force, and activation pattern of the muscles of the core to maintain core stability. It is important to understand that these systems work together with constant communication and interaction.

Spinal “control” may be a better term than spinal “stability.” Core exercises are often used in an attempt to “stabilize” the spine or torso. This implies that something in the spine could be “unstable.” This terminology can be interpreted negatively and in some cases cause someone to adopt poor movement patterns or stop activities all together in an attempt to avoid an injury due to “instability.” Maintaining mobility is almost always better than prolonged bed rest when it comes to low back pain.

The goals of core training include:

-

Controlling movement

-

Maintaining a neutral spinal position

-

Adequately transferring load during functional movements

There are different groups of muscles that work to accomplish these goals.

Looking for a suspension system for the home? Check out TRX Suspension offerings.

Looking for a suspension system for the home? Check out TRX Suspension offerings.

What is the Core?

There is more to the core than the ever elusive “6 pack abs.”

There is an inner unit that is located close to the spine and the outer unit that has a more global influence. There is also a myofascial sling system that plays a key role in controlling movement in the lumbo-pelvic complex and can be an effective addition to core training programs.

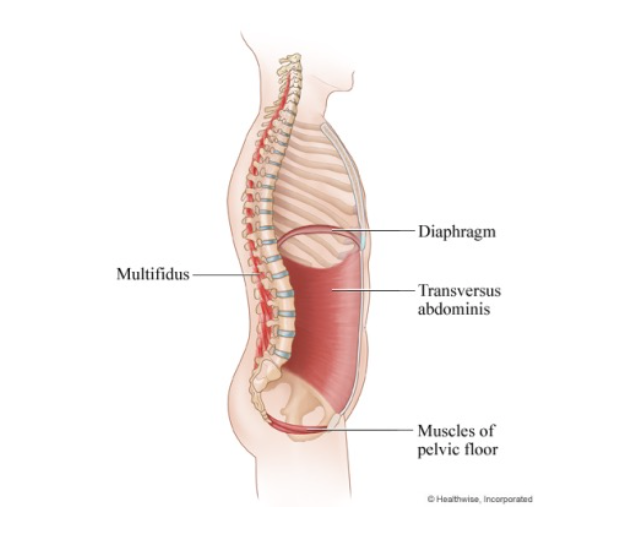

The inner unit consists of:

-

Diaphragm

-

Transversus abdominus muscle

-

Multifidus muscle

-

Muscles that make up the pelvic floor

Together, these structures help provide segmental stiffness and control intraabdominal pressure. They act as your body’s natural weight belt. Transversus abdominus and multifidus control movement at each spinal segment with prolonged tonic contractions. These low level tonic contractions occur in anticipation of limb movement.

Before you move your arm or leg, your core is already turned on and stays on to control spinal movements. Interestingly, in cases of low back pain these muscles have a delayed activation pattern and turn on after movement has already begun (Key, 2013). When training this group, it is a focus on neuromuscular control, timing, coordination, and endurance (Huxel Bliven, 2013).

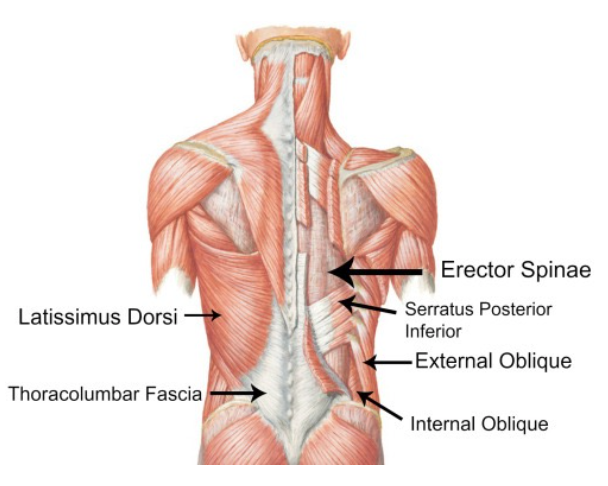

The outer unit is made up of the superficial abdominal muscles including:

-

Rectus abdominus

-

Internal and external obliques

-

Quadrates lumborum

-

Back extensor muscle group

These muscles have the ability to produce global trunk movements, but they work eccentrically to control spinal mobility (Huxel Bliven, 2013). Using these muscles in a bracing manner will stiffen the spine and prevent unwanted movements (McGill, 2010). Although the inner and outer units are made up of muscles that function differently, they work together to provide controlled and coordinated spinal movements.

In addition to the inner and outer units working together, they are also closely related to other muscular functions. The body is a complex and dynamic system that allows a wide range of movements. The spine and trunk form the foundation from which movement originates (Physiopedia, 2017). Some muscles work in conjunction with other muscles that are located in different areas of the body. These muscular connections are called myofascial slings.

Myofascial Slings

Myofascial slings are groups of tissues that are intimately connected and work together to produce controlled movements. The muscles within a myofascial sling are connected via fascia. When a muscle contracts, force is transmitted through structures of the sling to assist in transferring load within the trunk and spine (Physiopedia, 2017). When the muscles of the sling are working efficiently, movement can be better controlled, more force can be produced, and speed can be increased.

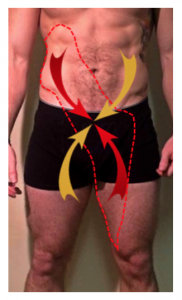

There Are Four Main Myofascial Slings:

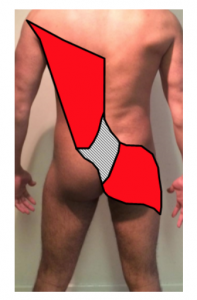

- The posterior oblique sling is made up of the latissimus dorsi muscle, the gluteus maximus, and the inter-connecting thoracolumbar fascia. This sling is most important during single leg standing activities and the stance phase of gait

2. The anterior oblique system consists of the internal and external obliques, connecting with contralateral adductor muscles via the adductor-abdominal fascia. These muscles work together to control movement and rotation at initial heel strike.

3. The deep longitudinal sling includes the erector spinae, multifidus, thoracolumbar facia, sacrotuberous ligament and the biceps femoris. This sling is important in maintaining control of the pelvis during functional activity such as returning to neutral after tying your shoes or lifting something off the floor.

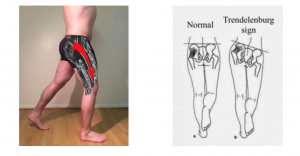

4. The lateral sling consists of the gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, tensor fascia latae and iliotibial band. This group of muscles works to keep the hips and pelvis level during functional tasks and single leg activities.

Would I Benefit From Core Training?

Low back pain can happen for a wide range of reasons; therefore one single approach may not be the answer. That is also why it is very important to seek professional guidance when low back pain does not resolve spontaneously. Your physical therapist can help identify the appropriate treatment for your injury.

Emerging evidence is indicating that the use of a classification approach to physical therapy can guide effective treatment plans (Fritz et al, 2007). Fritz et al. described recent research that helps to classify patients with low back pain into different categories with specific treatment guidelines. The classification approach involves screening for medical red flags, and using information from the history and examination to identify which treatment approach the patient will benefit from most.

The categories include: manipulation, specific exercise (flexion, extension, and lateral-shift patterns), stabilization (core), and traction (Fritz et al, 2007).

The stabilization category focuses on core training. Criteria that would indicate patients who might benefit from core training in this classification system include:

-

Younger age (<40)

-

Greater general flexibility (including post partum)

-

Abnormal movement patterns during lumbar range of motion (including painful catching or hinging)

-

Positive findings on physical tests (ie The Prone Instability Test)

In addition to these criteria, there are other factors that are seen clinically that might indicate a patient would benefit from core training.

Want to know exactly what you need to eat to feel better, lose weight, end cravings and have more energy? Check out the Viome gut microbiome and wellness kit.

Want to know exactly what you need to eat to feel better, lose weight, end cravings and have more energy? Check out the Viome gut microbiome and wellness kit.

As noted earlier, the muscles of the inner unit are programmed to start working before movement actually happens. This anticipatory action is disrupted in low back pain, resulting in altered timing of muscle contraction and less control of movement (Key, 2013). Patients exhibiting difficulties with activities that require load transfer (ie getting in and out of car) can benefit from core training due to increased strength and improved motor control.

Patients who encounter frequent episodes of low back pain may also have an improved outcome after core training. Low back pain is complex and requires proper assessment; a physical therapist can identify if core training is right for you.

Related Article: When You Should Go See A Physical Therapist

How Do I Train My Core Effectively?

Core training depends, first and foremost, on the individual patient’s needs and goals. Proper assessment will dictate the appropriate course of treatment. In general, core training programs can follow 4 stages:

Stage 1: Isolation of the Inner Unit

Early stage core training involves isolating, activating and training the muscles of the inner unit, while reducing activity of the outer unit.

Transversus Abdominus Activiation

-

Lay on your back with knees bent

-

Feel the muscle just inside the front bony pelvic bone

-

Try to make 1 mm space between your stomach and waistband by drawing your belly button in toward the spine (there should be minimal movements of the abdomen)

-

Goal is to hold for 10 seconds, 10 times

Enhance the intensity of your workout with HyperWear Gear and save space with their SandBell Weights.

Enhance the intensity of your workout with HyperWear Gear and save space with their SandBell Weights.

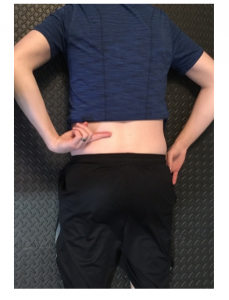

Multifidus Activation

-

Lay on your stomach

-

Try to swell the muscle that runs along the lower part of your spine by imagining that you are trying to balance a golf ball on a tee

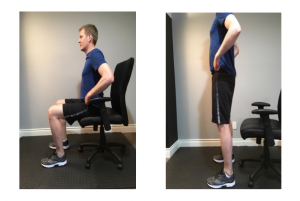

Stage 2: Inner Unit Control During Light Functional Activity

Maintain inner unit activation in different positions and during activities of daily living: getting in and out of the car, sitting, sit to stand, reaching up for dishes in the cupboard, etc.

Stage 3: Inner unit control while training the outer unit

Inner unit activation with moderate functional activity and outer unit training

Birddog Exercise

-

Starting on hands and knees

-

Activate inner unit

-

Raise opposite arm and leg and maintain position, then do other sides

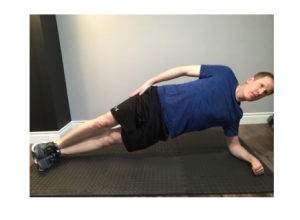

Side plank

-

Lay on your side

-

Activate inner unit

-

Prop up on elbow and feet (or knee if too challenging) and maintain plank position

Partial Curl up

-

Place half roll or rolled towel (or hands) under lower back

-

Activate inner unit and curl up one vertebrae at a time only part way

Stage 4: Functional Retraining

Maintain inner and outer unit activation while adding in elements of reduced base of support, unsteady surface, specific functional activities and incorporating myofascial sling exercises

- The posterior oblique sling is made up of the latissimus dorsi muscle, the gluteus maximus, and the inter-connecting thoracolumbar fascia.

Lunge with Pull Down

– TheraBand attached at the top of the door

– Reverse lunge with pull down

2. The anterior oblique system consists of the internal and external obliques, connecting with contralateral adductor muscles via the adductor-abdominal fascia.

Oblique crunches with ball squeeze

-Squeeze a pillow (or ball) between knees as you do a small crunch with slight rotation

-This sling is also very active during hill sprints and running on sand as it works to control movement at initial contact.

3. The deep longitudinal sling includes the erector spinae, multifidus, thoracolumbar facia, sacrotuberous ligament and the biceps femoris.

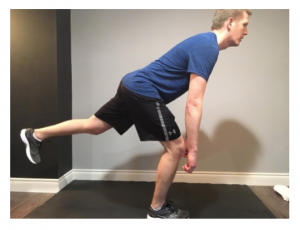

Single Leg Deadlift

-Keeping that knee slightly bent, perform a deadlift by bending at the hip, extending your free leg behind you for balance.

-Continue lowering as far as your balance allows, and then return to the upright position.

-As you improve lower until you are parallel to the ground.

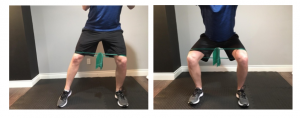

4. The lateral sling consists of the gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, tensor fascia latae and iliotibial band

Side Stepping with Squat

-Tie theraband around your knees

-Step to the side and then squat, keeping the knee over the ankle

Single Leg Squat (Progression)

-Perform a squat while standing on one leg

-Make sure to keep ankle, knee, hip all in a line

Conclusion

Lower back pain is a common occurrence. Determining the cause of pain and why the pain develops is very complex.

In some cases, dysfunction in the local and global core muscles can be a contributing factor to this pain. The low back, pelvis, and hip work together to move properly and transfer load effectively; failure to do so can lead to pain and dysfunction. The bones, discs, muscles, and nerves, all interact to maintain normal function (passive, active, and neural control systems). In low back pain this interaction can be impaired and will require intervention to improve control in the lower back, pelvic, and hip region.

The addition of core training with a focus on the inner and outer units, as well as, the myofascial sling system can be helpful in alleviating lower back pain.

Related Video:

You Might Like:

7 Key Exercises To Prevent Shoulder Injuries

Ryan Cross, B.A. Hons (Kin), MScPT, FCAMPT Registered Physiotherapist in Sarnia, Ontario, Canada Have you ever had difficulty reaching up to the top shelf or doing an overhead lift? Most people have encountered a shoulder...Strength Training Can Improve Chronic Plantar Fasciitis

Ryan Cross, B.A. Hons (Kin), MScPT, FCAMPT Registered Physiotherapist Do you feel sharp pain on the bottom of your heel during the first few steps you take in the morning? Is heel pain limiting progression...7 Ways To Prevent Running Injuries

Ryan Cross, B.A. Hons (Kin), MScPT, FCAMPT Registered Physiotherapist in Sarnia, Ontario, Canada Running is one of the most common activities that people participate in to maintain a healthy and active lifestyle. Running injuries happen...What Is The Fascia And Why Does It Matter?

Ryan Cross, B.A. Hons (Kin), MScPT, FCAMPT Registered Physiotherapist in Sarnia, Ontario, Canada For as much as we know about how the body works, there are still mysteries when it comes to anatomy and body...Avoid Back Pain & Stretch Your Hip Flexors | FastTwitchGrandma Tips & Tricks

Prolonged sitting can tighten your hip flexors and when you stand it pulls on your lumbar spine. This can cause severe back pain and muscle dysfunction. This hip flexor stretch is prescribed 2-3 times a...How To Treat 7 Common Running Injuries

Ryan Cross, B.A. Hons (Kin), MScPT, FCAMPT Registered Physiotherapist in Sarnia, Ontario, Canada Running is an activity that can provide many benefits. It improves cardiovascular function, aids in weight control, and can alleviate stress. Runners...References:

Cassidy JD, Carroll LJ, Cote P. 1998. The Saskatchewan Health and Back Pain Survey: The prevalence of low back pain and related disability in Saskatchewan Adults. Spine 17: 1860-1867.

Panjabi, M. The stabilizing system of the spine. Part I. Function, dysfunction, adaptation, and enhancement. Journal of Spinal Disorders, Volume 5, Issue 4, 1992. Pages 383-389.

Huxel Bliven, Kellie C., and Barton E. Anderson. “Core stability training for injury prevention.” Sports Health 5.6 (2013): 514-522.

Key, Josephine. “‘The core’: understanding it, and retraining its dysfunction.” Journal of bodywork and movement therapies 17.4 (2013): 541-559.

McGill, Stuart. “Core training: Evidence translating to better performance and injury prevention.” Strength & Conditioning Journal 32.3 (2010): 33-46.

Physio-Pedia. (Retrived: 2017, April 12). Anatomy Slings and Their Relationship to Low Back Pain. Retrieved from http://www.physio-pedia.com/Anatomy_Slings_and_Their_ Relationship_to_Low_Back_Pain

Fritz, Julie M., Joshua A. Cleland, and John D. Childs. “Subgrouping patients with low back pain: evolution of a classification approach to physical therapy.” journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy 37.6 (2007): 290-302.

Spinal Stability Diagram: http://www.physio-pedia.com/Anatomy_Slings_and_Their_Relationship_to_Low_Back_Pain#Posterior_Oblique_Sling

Inner Core Muscles Diagram: https://helloconfidencedotcom.files.wordpress.com/2015/03/inner-core-muscles-diagram.jpg

Outer Core Muscles Diagram: https://helloconfidencedotcom.files.wordpress.com/2015/03/inner-core-muscles-diagram.jpg

Posterior Oblique Sling: http://www.physio-pedia.com/Anatomy_Slings_and_Their_Relationship_to_Low_Back_ Pain#Posterior_Oblique_Sling

Posterior Oblique Sling-2: http://www.physio-pedia.com/Anatomy_Slings_and_Their_Relationship_to_Low_ Back_Pain#Posterior_Oblique_Sling

Posterior Oblique Sling-3: http://www.physio-pedia.com/Anatomy_Slings_and_Their_Relationship_to_Low_ Back_Pain#Posterior_Oblique_Sling

Posterior Oblique Sling-4: http://www.physio-pedia.com/Anatomy_Slings_and_Their_Relationship_to_Low_ Back_Pain#Posterior_Oblique_Sling