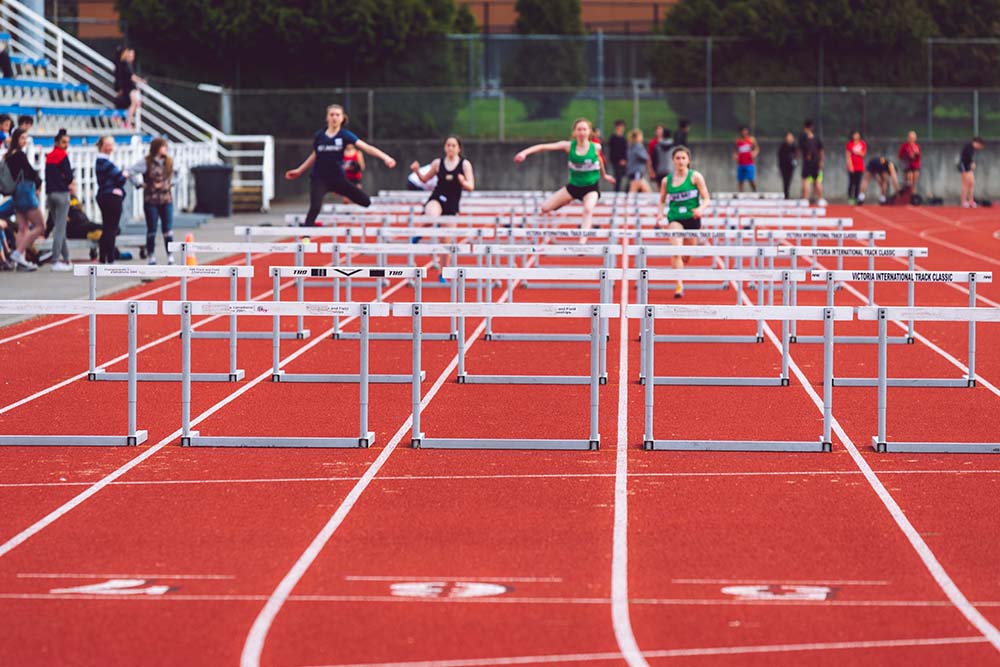

So You Want To Be A Sprinter? – Part 2

Evan Stevens

So You Want To Be A Sprinter? – Part 1

Part 2: Arms (& a small note about foot positioning)

So now that we have an understanding of how our legs move while sprinting from Part 1, we’re ready to hit the track, right? Not just yet. We are neglecting our upper bodies – our trunk and arms. Believe it or not, your arms and the way they move have a huge impact on how you run. The importance of arm action in sprinting is a hotly debated subject right now. Namely whether arms are used simply to correct for balance and postural changes, or, can also aid in driving the legs and momentum down the track. In The Mechanics of Sprinting and Hurdling (2010 edition) Dr. Ralph Mann notes that the legs, and not the arms, primarily dictate success in sprinting.

He is quoted in the article titled ‘A Farewell to Arms? The Debate Over Arm Swing Mechanics in Sprinting’ by Ken Jakalski that “Contrary to popular belief, superior arm action does not produce superior sprint performance. In fact, regardless of the quality of the sprinter, there is no significant difference in the arm action. If a sprinter could improve the horizontal velocity simply by moving the arms faster, then even old, out of shape coaches could run as fast as the elite sprinter since virtually everyone can move their arms fast enough to produce an elite level stride rate of five steps per seconds.” While he later qualifies that arms are important to the maintenance of balance, and aid in vertical lift, he stands by that arm swing isn’t nearly as important it sprinting as some make it out to be.

Get Those Arms Moving

Some would disagree with Dr. Mann’s explanation. Many feel that the arms help propel the sprinter down the track. The planar motion of the arm swing can help dictate the motion of the legs. Arms that swing mostly to the sides of the body without crossing the midline help to promote force generation in a straight line, down the track, as opposed to off to the sides where force might be directed if arms are flailing across a sprinter’s midpoint.

Hips create some rotational motion when they move – it is the nature of a ball and socket joint to rotate. Arm swing helps to correct the rotational motion generated by the hips and contain the motion to a single frame. Without arms acting to counterbalance the lower body, the trunk would go through torsional motion that would cause forces to be lost in different directions, and not all directed down the track. The problem for most when rationalizing the importance of arm swing in relation to power, however, is that at top speed, when a sprinter is erect, the backward swing of the arm counteracts the forward swing, essentially resulting in a net zero force.

Yet, when we thinking about what we have learned so far with the relationship of horizontal and vertical force, and we go back to Dr. Mann’s statement in regard to vertical lift, we can start to imagine the importance of arm swing in relation to sprinting. While it is true that arms are never going to be as important to sprinting as legs, we have to also understand that the arms help promote the conservation of momentum.

Sprinter Arms

We often hear coaches tell their athletes, “arms lead the legs – swing your arms!” But just how true is that? We have a bit of an understanding to the importance of arm swing – keeping your body in line, driving forces down the track, balance, and (as we will learn in the upcoming parts) driving power out of the starting blocks, but just how true is it that arms lead the legs? We read Dr. Mann’s take on it, that you can swing your arms as fast as you want but legs are always going to win, but then why do coaches still tell us to swing our arms more, especially as we start to tire out.

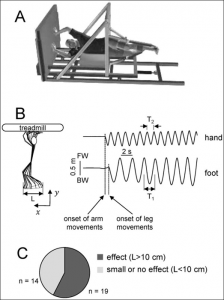

Well, the answer may lie more in our past – neural pathways that are remnants from when we took to walking on two legs. A 2014 study published in the Public Library of Science’s open access journal titled “Locomotor-Like Leg Movements Evoked by Rhythmic Arm Movements in Humans” described when the frequency of arm movement increased, so too did the frequency of leg movement.

They had subjects lay horizontally and placed a treadmill above their arms, within reach. They were then instructed to “walk on their hands” along the treadmill. As they did, the participants’ legs started to move as well, walking through the air, just as they would if they were walking upright on solid ground; opposite arm, opposite leg. The authors remarked: “We found that moving the arms rhythmically on an overhead treadmill, as in hand-walking, often elicited automatic, alternating movements of the legs in a significant proportion of tested subjects as in normal walking, the frequency of leg movements increased with increasing frequency of arm movements during hand-walking.” They concluded that the concurrent movement is active (neural) rather than mechanical (passive).

Faster Arms ≠ Faster Legs

Does this mean that faster moving arms will mean faster moving legs? Kind of, but not entirely. The authors note that the movements could be remnants of quadrupedal motion and the need for our ancestors’ need to use diagonal limb couplets for motion (opposite arm, opposite leg moving in tandem to move). This ancient neural connection linking the arms and legs is part of the reason why we move our legs with our arms but the authors also noted that leg movement was lower in frequency than the arm movements. So there is a link, but arms don’t necessarily lead the legs, they can just help. The predominant theory as to why our arms move the way they do with our legs (other than for balance and conservation of momentum in relation to sprinting) is because of neural circuits that our body uses without the need for sensory input.

Does this mean that faster moving arms will mean faster moving legs? Kind of, but not entirely. The authors note that the movements could be remnants of quadrupedal motion and the need for our ancestors’ need to use diagonal limb couplets for motion (opposite arm, opposite leg moving in tandem to move). This ancient neural connection linking the arms and legs is part of the reason why we move our legs with our arms but the authors also noted that leg movement was lower in frequency than the arm movements. So there is a link, but arms don’t necessarily lead the legs, they can just help. The predominant theory as to why our arms move the way they do with our legs (other than for balance and conservation of momentum in relation to sprinting) is because of neural circuits that our body uses without the need for sensory input.

These neural circuits, called Central Pattern Generators (CPGs) provide specific timing information when information from elsewhere (the muscles) are not available. CPGs are important for running and sprinting form because they act as body cues when information from elsewhere in the body is not working as we want. If a sprinter’s legs are lacking certain leg cues (sensory inputs), be it knees coming in or heels lifting but not driving through, CPGs could instead work with the arms and drive running form through cues from the arm swing. The rhythmic motion of the arms could carry the legs when cues aren’t quite working.

Find Your Rhythm

Arm swing and its contribution to overall performance is a hotly debated topic. Does it matter as much as some make it out to be? Does spending time focusing on arm swing at a practice take away time that could be used focusing on where speed and power comes from – the legs? I don’t think so. There is still a lot of work to be done, statistics to be calculated and different methodologies to be tested. Yet I think that proper arm swing can only help good running and sprinting form, from the conservation of momentum, to aiding in balance, and help the body provide positional feedback to itself as it moves.

Foot Positioning

One smaller note to add to our discussion about proper form and technique is the often neglected, yet important aspect of foot positioning. While sprinting we want our ankles to be dorsiflexed, or the flexion of the foot towards the shin. This allows energy to be stored in the “strained muscle” and allows for better use of the leg’s natural spring, comprised of the plantar tendon under the foot, the Achilles tendon at the back of the ankle, and the large calf muscles. Dorsiflexed ankles allow mechanical energy to be stored as elastic energy as the foot comes off the ground and cycles back down into the next stride. Storing this force allows for faster, more powerful turn over, greater stride length and frequency, and faster running.

Good Positioning Generates Power

Why the feet and arms go together is because the feet dictate the need for the arms to stabilize and prevent rotation. While sprinting feet fall outside the centre line of mass. This causes torque, or a turning force to run up the leg to the hip. The hips will rotate towards the push off foot and unless this rotation is counteracted by the arms, you get a “spinning sprinter.” The more you can get your foot to fall pointed down the track, and not pointed outwards, the less you will have to work with the rotational force as well, as the toes pointed outwards causes the stored elastic energy to be transferred through that direction more.

Keeping the feet in good positioning generates power and prevents too much torque so that the arms do not have to come across the midpoint of the body (usually a good indicator that something is going on in the lower body).

Related Video:

You Might Like: