The Risks and Causes of ACL Injury and How You Can Prevent Them

Hunter Bennett

When it comes to improving athletic performance (and general health for that matter), there is nothing that derails your progress more than an injury.

While many injuries can be trained around in some capacity, they often result in the cessation of improvement, an inability to both compete and perform certain exercises, and an associated decline in motivation and self-esteem. And none are more detrimental than an ACL injury.

What is an ACL injury?

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) connects your femur to your tibia, thus providing essential stability to the knee joint via completely passive mechanisms. It essentially prevents the tibia from sliding forward relative to the femur during movement, while also resisting potentially harmful rotational movements of the knee.

If you didn’t have one, your knee would be unstable, in which you would be at a heightened risk of several lower limb ligament, muscle, and joint injuries.

Taking all of this into consideration, an ACL injury simply describes an injury that occurs to this extremely important ligament. An ACL injury can be separated into one of three categories, depending on its severity:

- Grade 1: occurs when the fibers of the ligament are stretched but do not tear. While painful, for the most part, the knee will remain stable and surgery will not

be required.

be required. - Grade 2: occurs when the ligament is partially torn. This results in a greater loss of stability, and often more painful. Surgery may or may not be required depending on the severity of the tear.

- Grade 3: are the most common type of ACL injuries among athletic populations, which describes a complete rupture of the ligament. Swelling and pain are often immediate and severe. Reconstructive surgery is often required in this scenario, which often requires an 8-12-month rehabilitation period.

It is also important to note that around one-half of ACL injuries also occur with associated damage to another part of the knee, such as the importance of this key ligament.

What causes ACL injuries?

While ACL injuries can occur in response to a contact injury, they are most often non-contact in nature. In this manner, they most often occur during the ground reaction phase of jumping and landing tasks, rapid change of direction movements, and single leg bounding activities. During these key movements, the knee is under a high amount of load.

In an ideal world, the muscles that act on both the hip and knee would help absorb this load, reduce any undesirable movement at the knee, and keep the lower limb in optimal alignment. But unfortunately, this is often much easier said than done.

In these scenarios, the knee tends to fall into internal rotation (think of the knee collapsing inwards) while the lower shank glides too far forward, placing the ACL under extreme load, and causing it to rupture (Kobayashi, 2010).

Not nice.

Related Article: How To Treat 7 Common Running Injuries

Who is at high risk for ACL injury?

There are a number of key risk factors associated with an increased risk of ACL injury (Hewett, 2016).

Obviously, those individuals who play sports that require a lot of jumping, landing, and rapid change of directions are going to be at an increased risk of ACL injury compared to those who do not. These movements have the tendency to place the knee in undesirable positions, which results in heightened injury risk.

Poor core strength and trunk control have previously been identified as a risk factor for ACL injury, as has single leg postural control – both of which relate to your capacity to move and control your body during powerful athletic tasks.

Similarly, lower limb muscular strength imbalances have also been shown to impact ACL injury risk.

More specifically, the relative weakness of the hamstrings compared to the quadriceps can result in increased forward translation of the tibia on the femur, which as we know, can place the ACL under increased load.

Similarly, weakness of the muscles that act on the hip (think gluteus medius, gluteus maximus, and the external rotators) can allow the knee to rotate inwards, which again, contributes to the acute incidence of ACL injury.

In conjunction with the above, asymmetrical lower body strength has also been identified as a potential risk factor for ACL injury. With this in mind, if one leg is significantly weaker than the other in any capacity, it is likely to be at an increased risk.

I should also note that there is one more, and it is a bit of a big one.

Gender.

Can gender influence ACL injuries?

Females that compete in high impact sports suffer ACL injuries at a rate somewhere between 4 and 6 times greater than their male counterpart (Hewett, 2005).

Yep, you heard that right – females are 4-6 times more likely to suffer an ACL injury.

Isn’t that crazy?

Now while this has been hypothesized to be the result of several different factors, in my mind, there are two main ones that require consideration.

Firstly, females have a key structural difference within their pelvis when compared to males, which presents itself as a greater quadriceps angle (also known as the ‘Q angle).

The Q angle is the angle formed by a line drawn from the anterior portion of the pelvis to the center of the knee, and then a line from the center of the knee to the tibial tuberosity (the large protrusion from the lower shank).

This increased angle is the result of females having wider hips than their male counterparts, which can increase the risk of the knee collapsing into valgus, and therefore resulting in an increased risk of ACL rupture (Kızılgöz, 2018).

Not ideal.

Secondly, female athletes have been traditionally underfunded in comparison to their male counterparts. This means that they, in turn, have traditionally received less quality coaching, and less effective injury prevention programs.

As such, when this is combined with the key anatomical differences observed at the pelvis, I truly believe that it creates the perfect storm for ACL injuries.

Do landing mechanics impact ACL injury risk?

With all the above information, it is also important to touch on landing mechanics. Not only do they play an important role in ACL injury risk, but they are also modifiable – meaning that we can actually improve them through training.

We have already discussed that ACL injuries are most likely to occur during jumping and bounding tasks and during rapid changes of direction. But it is important to note that they are unlikely to occur during the jump itself, but rather during the landing.

Those individuals who land with a greater knee abduction angle (AKA, with their knee collapsing in more) are at a much greater risk of ACL injuries than those who do not (Ishida, 2018).

This collapse inward is indicative of weak hip and trunk musculature, and an inability of the muscular system to absorb the ground contact forces associated with landing. As a result, the force is solely distributed into the passive structures of the knee (such as the ACL…), which are also placed in a rather vulnerable position.

Rupture results…

What are the expected outcomes after an ACL repair?

The most common treatment modality to a complete ACL rupture is reconstructive surgery, in which the ACL is repaired using either a grafted piece of connective tissue from somewhere else in the body (the patella and hamstring tendons are quite common), or a newly developed synthetic material.

There is currently no standardized return to play procedure for ACL surgery, however, there are five common stages that a rehabilitation program tends to follow (Cavanaugh, 2017).

- Stage 1 (post-operative phase 1): Lasts for the first two weeks post-surgery, with the focus on limiting swelling, maintaining quadriceps strength, activation, and function through passive extension, and maintaining knee range of motion up to 90 degrees of flexion (and no further).

- Stage 2 (post-operative phase 2): Runs from weeks 2-6 after surgery, with the primary goals of returning knee flexion range of motion up to 130 degrees. With this, we want to restore normal gait and the ability to ascend stairs without pain. Weight bearing should be gradual and progressive.

- Stage 3 (post-operative phase 3): Runs from weeks 6-14. Goals include restoring full knee range of motion, improving lower body strength and endurance, and developing the ability to descend stairs without pain and under control. During this stage, the introduction of lower body strength and proprioception exercises is encouraged.

- Stage 4 (post-operative phase 4): Runs from weeks 14-22. Goals include developing the ability to run pain-free, maximizing lower limb strength and flexibility to manage demands of daily living, and reducing limb strength asymmetry. During this stage, running can commence, as can plyometric, change of direction, and agility-based exercises.

- Stage 5 (post-operative phase 5): Runs from weeks 22 until return to sport (which can be between 8 and 12 months after surgery). Goals include improving movement quality, maximizing strength and function to meet game demands, and eliminating limb asymmetry. Advanced plyometric and strength programs are recommended, as is the introduction of sport specific training.

If I were to put it simply, after ACL reconstructive surgery you are in for a long recovery process, essentially ensuring that by the time you are ready to return to a sport you are better prepared for the demands of that sport than you were in the first place.

Or alternatively, we can focus on prevention, limiting the likelihood of an injury occurring in the first place.

Sounds like a better option, right?

Related Article: Reduce Muscle Fatigue With Foam Rolling

How can I prevent ACL injuries?

Taking all the above into consideration, there are several different things that we need to prioritize when it comes to ACL injury prevention (Nessler, 2017).

We need to develop adequate lower limb muscular strength. This means training the quadriceps, hamstrings, and gluteal muscle groups in isolation to ensure that they have the foundational strength required to maintain good lower limb alignment during athletic tasks.

Once this has been developed, its time to integrate these muscle groups into more complex movement patterns that underpin those athletic tasks, such as squats, lunges, split squats, and deadlifts, to further develop functional strength.

With this, the development of core strength should also be a priority to further improve the body’s ability to absorb and distribute force.

In conjunction with strength development, implementing plyometric exercises with perfect technique is essential to teach you how to absorb force appropriately upon landing, while maintaining good knee alignment.

Plyometric exercises should progress from bilateral movements to unilateral hopping movements, and should also be symmetrical when comparing limbs.

And finally, these should be combined with various reactive neuromuscular drills that require rapid changes of direction and unpredictable jumping and landing movements. These activities closely replicate sporting demands and therefore prepare the individual for any unexpected game situations that may increase ACL injury risk.

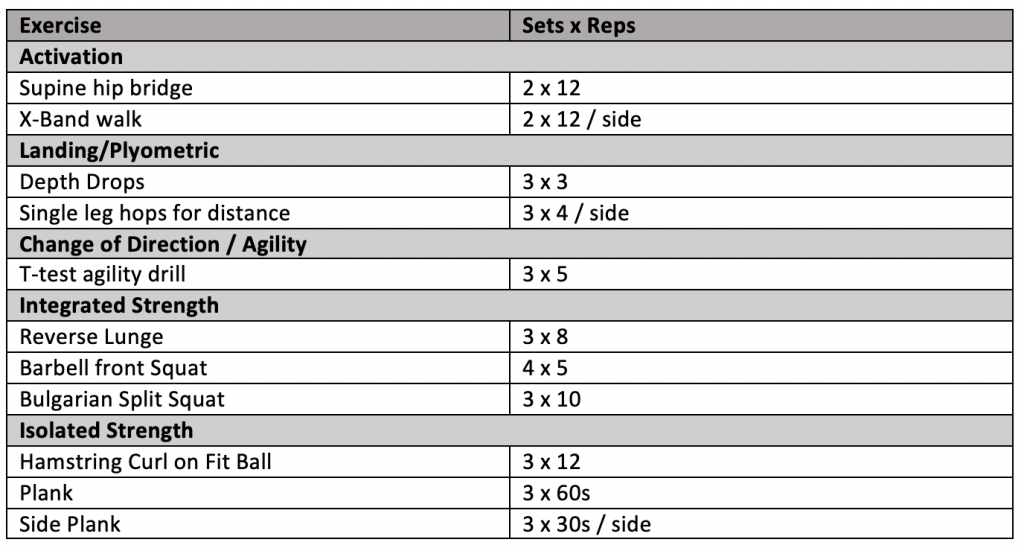

ACL Injury Prevention Program

Using the information from the above section, I have put together a short ACL injury prevention program that can be completed twice per week. I should note that this will not be suitable for everyone, however, it does provide a nice example of how an ACL prevention program can be put together.

Take Home Message

ACL injuries are one of the most common to plague athletic populations, resulting in a huge amount of time lost in conjunction with a long and intensive recovery period. While there are several risk factors that can contribute to ACL injury, there are also a number of preventive steps that can be put in place to help mitigate their risk of occurring.

So, take the time to train appropriately and prepare for your sport, ensuring that you don’t become another ACL injury statistic during the process.

References

Kobayashi, Hirokazu, et al. “Mechanisms of the anterior cruciate ligament injury in sports activities: a twenty-year clinical research of 1,700 athletes.” Journal of sports science & medicine 9.4 (2010): 669.

Hewett, Timothy E., et al. “Mechanisms, prediction, and prevention of ACL injuries: cut risk with three sharpened and validated tools.” Journal of Orthopaedic Research 34.11 (2016): 1843-1855.

Hewett, Timothy E., et al. “Biomechanical measures of neuromuscular control and valgus loading of the knee predict anterior cruciate ligament injury risk in female athletes: a prospective study.” The American journal of sports medicine 33.4 (2005): 492-501.

Kızılgöz, Volkan, et al. “Analysis of the risk factors for anterior cruciate ligament injury: an investigation of structural tendencies.” Clinical imaging 50 (2018): 20-30.

Ishida, Tomoya, et al. “The effects of a subsequent jump on the knee abduction angle during the early landing phase.” BMC musculoskeletal disorders 19.1 (2018): 379.

Cavanaugh, John T., and Matthew Powers. “ACL Rehabilitation Progression: Where Are We Now?.” Current reviews in musculoskeletal medicine 10.3 (2017): 289-296.

Nessler, Trent, Linda Denney, and Justin Sampley. “ACL injury prevention: what does research tell us?.” Current reviews in musculoskeletal medicine 10.3 (2017): 281-288.

You Might Like: