Don’t Let Your Twisted Ankle Become A Chronic Problem

Ryan Cross

It seems as though everyone has twisted their ankle at some point in life. It can happen walking across the street, going down stairs, or during any recreational activity.

Some reports estimate that over 23,000 ankle sprains occur every day in the United States (Hertel, 2002). Since this injury is so common and seemingly minor in nature, it is estimated that 55% of people who suffer an ankle sprain do not seek treatment from an appropriate health care professional (Hertel, 2002). Interestingly, the incidence of residual symptoms and recurrent injury following an ankle sprain is reported to be approximately 54%. (Pourkazemi et al, 2014).

Last week I discussed how hip weakness is a risk factor associated with ankle sprains. This week I would like to explain how it is common to have residual symptoms after an ankle sprain and how to avoid those symptoms.

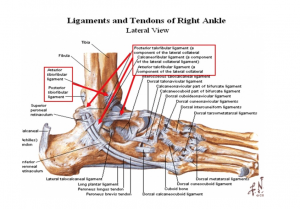

ANATOMY OF AN ANKLE SPRAIN

The most common type of ankle sprain occurs when the ankle and foot turn in. This places the most stress on the ligaments located on the outside of the ankle.

Passive stability of the ankle is provided by 3 ligaments laterally and one complex ligament medially. Of the 3 ligaments stabilizing the lateral aspect of the ankle, the anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL) is the most common ligament to be injured. The ATFL prevents anterior displacement of the talus bone and excessive inversion and internal rotation of the foot/ankle complex. The strain in the ATFL increases as the ankle moves from dorsiflexion into plantar flexion. The forceful combination of these movements creates the ankle sprain. Dynamic stability is primarily provided by the peroneus longus and brevis muscles. When these muscles contract, they pull the foot and ankle in the opposite direction of how lateral ankle sprains occur.

Proprioception and neuromuscular control

are also important factors to consider when discussing ankle sprains and dynamic stability. Proprioception is related to the body’s ability to determine where a joint or body part is in relation to the environment. Neuromuscular control involves the body’s ability to coordinate actions in an attempt to provide dynamic stability and smooth movements. Deficits in passive and dynamic stability result after an ankle sprain.

Related Article: Ankle Sprains Start In The Hip

WHY CAN THIS INJURY BECOME A PERSISTENT PROBLEM?

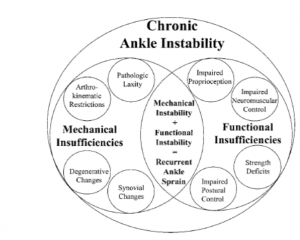

There are two factors that contribute to why ankle sprains become a chronic issue: mechanical instability and functional instability (Hertel, 2002).

Mechanical instability

involves the anatomical changes that occur as a result of the initial injury and the disruption of the ligament itself. This includes excessive joint mobility, altered joint mechanics, and the development of degenerative joint disease. Excessive joint mobility is directly related to the severity of the sprain of the ligament, ranging from a relatively minor grade 1 to a severe grade 3. The forces placed on the ankle and foot complex during a sprain can also alter the mechanics of how the joints move. When the ATFL is injured, it pulls the distal fibula forward which changes the resting position of the ligament and can prevent full dorsiflexion range of motion. Without full dorsiflexion, the ankle cannot attain closed pack position, which predisposes recurrent ankle sprains (Hertel, 2002). These mechanical changes can contribute to early onset of degenerative joint disease due to alterations in the forces placed on the joint.

Functional instability

relates to alterations in the body’s ability to dynamically stabilize the ankle during functional activity. Deficits are seen in proprioception, neuromuscular control, postural control and strength (Hertel, 2002). Joint receptors within the ligament are important for maintaining proper proprioception at the joint. This process is adversely affected when the ligament is injured. This will also affect the neuromuscular control of the joint and cause altered movement patterns to maintain dynamic stability. Together, these changes negatively impact effective postural control. If you stand on one foot, you will notice your foot “wobble” from side to side to maintain your balance. This is called an “ankle strategy,” but after an ankle sprain, individuals tend to use a “hip strategy” which is less efficient and could lead to recurrent injury (Hertel, 2002).

HOW TO AVOID CHRONIC PROBLEMS?

An ankle sprain presents initially with pain, swelling, and limited function. This will typically resolve in a matter of weeks. The challenge for many clinicians is to educate the patient on the importance of continuing to participate in a rehabilitation program. To prevent a “minor” ankle sprain from becoming a recurrent problem, the first step is a proper assessment with an appropriate health care professional.

A physiotherapist will start with a thorough assessment that includes getting baseline measurements of range of motion (ROM), balance, strength, and functional status. Next, it is important to come up with goals that you hope to accomplish with treatment, including functional status, return to work, and return to sport. This will help to guide the individualized treatment plan.

Treatment

Treatment will involve hands on manual therapy to address joint restrictions, joint positioning, and painful/threatening movements. Joint mobilizations can help patients regain dorsiflexion range of motion faster (Hertel, 2002). Flexibility and range of motion exercises will to improve mobility and maintain the gains achieved with the manual therapy.

A comprehensive rehabilitation program will also emphasize proprioceptive, neuromuscular control, and balance training in an attempt to reduce the risk of recurrent ankle sprains.

Strength exercises will be included to improve dynamic stability. It is important that strength isn’t just focused around the ankle, but the entire kinetic chain.

Related Article: When You Should Go See A Physical Therapist

Studies

Doherty et al studied patients after their first ankle sprain to determine which factors contribute to chronic issues and which patients are able to “cope.” They studied patients during landing tasks and it was found that patients who develop chronic problems have altered hip mechanics when landing from a height (Doherty et al, 2016). In another study, people with chronic ankle instability were shown to have weakness in hip abduction strength testing (Friel et al, 2006). These studies highlight the importance of addressing proximal joints during the development of a treatment plan. As your status improves, the focus of treatment will shift to return to sport with exercises focusing on speed, endurance, and agility training.

TAKEAWAY

Although an ankle sprain appears to be minor and resolve on its own, it is important to understand the underlying issues that can arise with this injury. This injury has a high incidence of chronic problems that could be a result of not managing it properly. With appropriate assessment and treatment, an ankle sprain doesn’t have to keep you on sidelines long term.

References

Hertel, Jay. “Functional anatomy, pathomechanics, and pathophysiology of lateral ankle instability.” Journal of athletic training 37.4 (2002): 364.

Pourkazemi, Fereshteh, et al. “Predictors of chronic ankle instability after an index lateral ankle sprain: a systematic review.” Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport 17.6 (2014): 568-573.

Doherty, Cailbhe, et al. “Single-leg drop landing movement strategies in participants with chronic ankle instability compared with lateral ankle sprain ‘copers’.” Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy 24.4 (2016): 1049-1059.

Friel, Karen, et al. “Ipsilateral hip abductor weakness after inversion ankle sprain.” Journal of athletic training 41.1 (2006): 74.

Ankle Photo Credit: https://www.anatomylibrary.us/anatomy-ankle-tendons

Diagram: Hertel, 2002

You Might Like: