The Importance of Food: How Should I Eat?

Author: Evan Stevens, MSc in Nutritional Science

In my previous article, titled “What Should I Eat – Part 1” I introduced the idea that the question of “what” should really be a question of “how.” People’s bodies change and age at different rates, different activities call for different dietary needs, and I left it off with an idea that healthcare and nutrition should be focusing on an individualized approach to feeding people and keeping them healthy. Two people can eat the exact same meal, and because of their individual profiles can expect different outcomes from the food. Differences in genetics (which determines the basic limits on metabolic function), conditioning (which is the impact of lifestyle choices at various life stages can modulate genetics) and environmental influences constitute each person’s individual profile, which is why “what should I eat” becomes a more difficult question to answer.

In my previous article, titled “What Should I Eat – Part 1” I introduced the idea that the question of “what” should really be a question of “how.” People’s bodies change and age at different rates, different activities call for different dietary needs, and I left it off with an idea that healthcare and nutrition should be focusing on an individualized approach to feeding people and keeping them healthy. Two people can eat the exact same meal, and because of their individual profiles can expect different outcomes from the food. Differences in genetics (which determines the basic limits on metabolic function), conditioning (which is the impact of lifestyle choices at various life stages can modulate genetics) and environmental influences constitute each person’s individual profile, which is why “what should I eat” becomes a more difficult question to answer.

There are, what most consider, two arms of this individualized approach to nutrition healthcare. The arm that most are probably familiar with are genes, your genetic code. Genes can dictate what you can and can’t eat, how you react to certain foods and which foods may be more rewarding to you in terms of energy and micronutrient availability.

Genes not only code for enzymes which help break down certain foods and release valuable micronutrients, but can also dictate energy metabolism, hunger responses, muscle growth and a host of other factors that contribute to health, performance, and well-being. This genetic approach to food and nutrition is the basis of a highly interesting and growing field of research called nutrigenomics that not only studies how genes affect our food choice, but also how food can affect gene expression. While we will return to the topic of nutrigenomics in due course, the focus of this paper is on that lesser known second arm of individualized food and nutrition – our gut microbiome.

The organisms that live within our gut have genes of their own which can lead to the creation of different metabolites and dietary intermediates that affect our own body’s usage of the food. Some bacteria possess genes that can create metabolites that harm our body and others have genes that produce metabolites that may have a beneficial effect on our body. These good and bad bacteria compete for resources, and if our diet is “poor” it gives the competitive edge to the “bad” bacteria.

The metabolites that are created by the bad bacteria may be of little to no use for us from a nutritional standpoint which can cause nutrient or dietary insufficiencies, or can cause metabolic damage, which can lead to inflammatory diseases. Our gut microbiomes are also special because they are individual to us; no two people will ever have the exact same gut microbiota profile. Our profiles can be changed through the use of prebiotics and probiotics that support the growth of certain kinds of anti-inflammatory microorganisms, but the genetic profile of the organisms and the different types will still remain unique to you.

So where does this individuality truly fit into the context of human health? Well, as you age, you are at an increased likelihood of several health issues, inflammatory-related issues being of main concern – cancer, Type II diabetes, arthritis, inflammation-induced memory issues and some auto-immune diseases among others. These issues have a huge impact on the quality of life, as well as your ability to perform, workout, or improve your fitness. One of the easiest measures of overall health in the context of ageing is blood glucose levels as measured by postprandial (post-meal) glycemic responses (PPGRs). Postprandial hyperglycemia (high blood sugar after a meal) is an independent risk factor for Type-II diabetes, cancer, inflammatory diseases, and a host of other health issues that only increase with age.

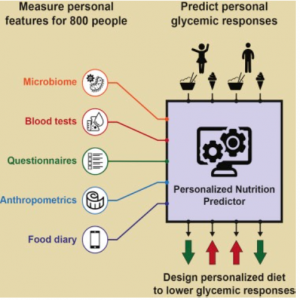

Although the importance of the PPGR is well documented, there exists no real method of predicting these responses to food. Set carbohydrate meal studies in the context of weight loss, cardiovascular risk factors, and overall health, regardless of time of consumption and activity level have yielded mixed results. Factor in real meals without set glycemic loads and the results vary even greater. While genetic differences, lifestyle choices, insulin sensitivity and other enzymatic activities may account for some of the differences, ascribing set PPGRs and glycemic loads to certain foods cannot fully describe the high-degree of variability in response between similar individuals when challenged with the same type of food. This has lead scientists to hypothesize that the gut microbiome has a large role in individual health and a recent article published in Cell aimed to look at the variability in PPGRs of individuals.

The researchers tested the PPGRs in an 800-person cohort of non-diabetic, characteristically population (54% overweight, 22% obese, with age ranges from 18-70) individuals who were instructed to log their activity and food intake on a smart-phone friendly web app developed by the researchers while participants were hooked up

to a continuous glucose monitor (a device which provides real-time blood glucose measures through the day and night). Participants were instructed to maintain their regular daily activities while on the glucose monitors save for the first meal of the day, in which they were provided one of four standardized meals containing 50g of carbohydrates.

to a continuous glucose monitor (a device which provides real-time blood glucose measures through the day and night). Participants were instructed to maintain their regular daily activities while on the glucose monitors save for the first meal of the day, in which they were provided one of four standardized meals containing 50g of carbohydrates.

Over the course of the study, the researchers logged a total of 10,000,000 calories allowing the researchers a global view of the cohort’s dietary intake. This allowed the researchers to better see individual caloric make-up of meals and account for variability in each person’s diet. What the researchers discovered, when looking at the data from selected individuals from the cohort with validated data, was the variability in the glucose responses even after standardized meals – people who were eating the exact same meals and who lived similar lifestyles and had similar overall caloric breakdowns of their other meals had widely different individual PPGRs.

The researchers found that although there was very little variability within a person meal to meal, between individuals, the exact same meal had significant differences. Some people responded to white bread with butter at an average of 15 mg/dl*h where as others responded at 79 mg/dl*h. Stool samples were collected from individuals to analyze the types of bacteria present/ bacterial composition of their microbiome as well and after bacterial assessment using the resources from the Human Microbiome Project it was found that the gut microbiome between individuals who responded either at the low end of the glucose response or the high end were wildly different. Even though these people were very similar in terms of diet, lifestyle, and even genetic background (all of Israeli descent), their individual responses to dietary challenges were greatly different, which the researchers attributed to the differences in their microbiome.

With these findings in hand, the researchers then sought to determine if individual PPGRs could be altered through dietary intervention. With a new cohort of 26 individuals, baseline measurement were taken and each person was given a set dietary plan by a dietitian, not wildly different than their regular diets, which they were instructed to follow for a number of weeks (each with a week off the intervention separating the intervention weeks) while hooked up to the continuous glucose monitor.

These personalized diets that were tailored to the person’s microbiome (as determined by the Human Microbiome Project) lowered the number of glucose spikes, as well as other factors of metabolic disease such as inflammatory cytokines. These findings show that while both baseline microbiota composition and personalized dietary intervention vary between individuals, several consistent microbial changes may be induced by dietary intervention with a consistent effect on dietary risk factors such as PPGR.

The importance of maintaining one’s gut health is imperative to longevity and overall health. Gut health has a huge impact on inflammatory markers, and has been linked to a number of age-related maladies such as cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s, arthritis, and diabetes. So if it is so important, what can you do?

Outside of getting your stools collected and having a specialist profile your microbiome profile and tell you what you should and shouldn’t eat, there are only a few things that can help. Avoiding pro-inflammatory foods – foods that are high in simple sugars, fats or adhering to a new “gut friendly” dietary regime that calls for a strict decrease or elimination of Fermentable Oligo-, Di-, Mono-saccharides And Polyols (common carbohydrates found in a western diet, called FODMAPs), or by supplementing with prebiotics and probiotics will help.

But there is emerging evidence to suggest that certain types of exercise have a beneficial effect on the gut microbiome, and the profile of anti- or pro-inflammatory microbes. Moderate exercise has been linked to improved gut health by  reducing transient stool time, thus reducing the prolonged contact of pathogens with the gastrointestinal mucus layer and circulatory system. Prolonged exhaustive exercise, however, has been predicted to cause gastrointestinal disturbances from toxicity caused by decreased blood flow to the area and microbe translocation to the bloodstream.

reducing transient stool time, thus reducing the prolonged contact of pathogens with the gastrointestinal mucus layer and circulatory system. Prolonged exhaustive exercise, however, has been predicted to cause gastrointestinal disturbances from toxicity caused by decreased blood flow to the area and microbe translocation to the bloodstream.

Preliminary data done in mice have shown that exercise of any type, when given a diverse food source had greatly improved the diversity of anti-inflammatory microbes. The more diverse the microbiome, the better you are to handle food challenges, and the more anti-inflammatory microbes, the better you are to prevent age-related health declines.

This hugely interesting, new field of individualized nutrition and gut health has a long way to go. Better and easier ways for a person to know, understand, and work towards optimal gut health are a must. More studies must be done on just how amenable the microbiome is to change, and to what degree and to how long treatment with prebiotics and probiotics is effective. The interaction of how exercise influences gut health is an even newer revelation and needs more preliminary data and human studies to understand the hows and whys.

The potential for improved health into later years, that nutrition can be catered in an individual way to optimize health and reduce age-related inflammatory diseases, and that exercise could be a vital component to all this cannot be ignored. Improving your gut microbiome, reducing inflammation, improving cognition, improving muscle and joint function, all go together with the Fast Twitch Grandma mantra of physical activity and health into later years. Proper and individualized nutrition helps to improve gut health, which improves the ability to exercise and perform through reduction in inflammatory diseases, which in turn appears to cycle back and further promote gut health. Try to be more mindful of what you put down your throat. Your gut will thank you, your mind will thank you, and your performance in the pool, on the track, on the bike, or whatever your endeavours may be, will thank you too.

Sources:

Cook, M D et al. “Exercise And Gut Immune Function: Evidence Of Alterations In Colon Immune Cell Homeostasis And Microbiome Characteristics With Exercise Training”. Immunology and Cell Biology (2015)

NIH/National Human Genome Research Institute. “Human microbiome project: Diversity of human microbes greater than previously predicted.” ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 21 May 2010. <www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2010/05/100520141214.htm>.

Wu, Shaoguang et al. “A Human Colonic Commensal Promotes Colon Tumorigenesis Via Activation Of T Helper Type 17 T Cell Responses”. Nature Medicine 15.9 (2009): 1016-1022.

Zeevi, David et al. “Personalized Nutrition By Prediction Of Glycemic Responses”. Cell 163.5 (2015): 1079-1094.