A Better Night’s Sleep: The Statistics

Gillian White – MSc, PhD (C), University of Toronto, Department of Exercise Sciences

Sleep is not just a rest for our brain and body but is absolutely essential to our health and function.

Sleep deprivation has similar effects of alcohol on how our brain and body functions and, if prolonged enough, can actually result in death. 50-70 million Americans report a sleep disorder, with 25 million of those reporting obstructive sleep apnea1.

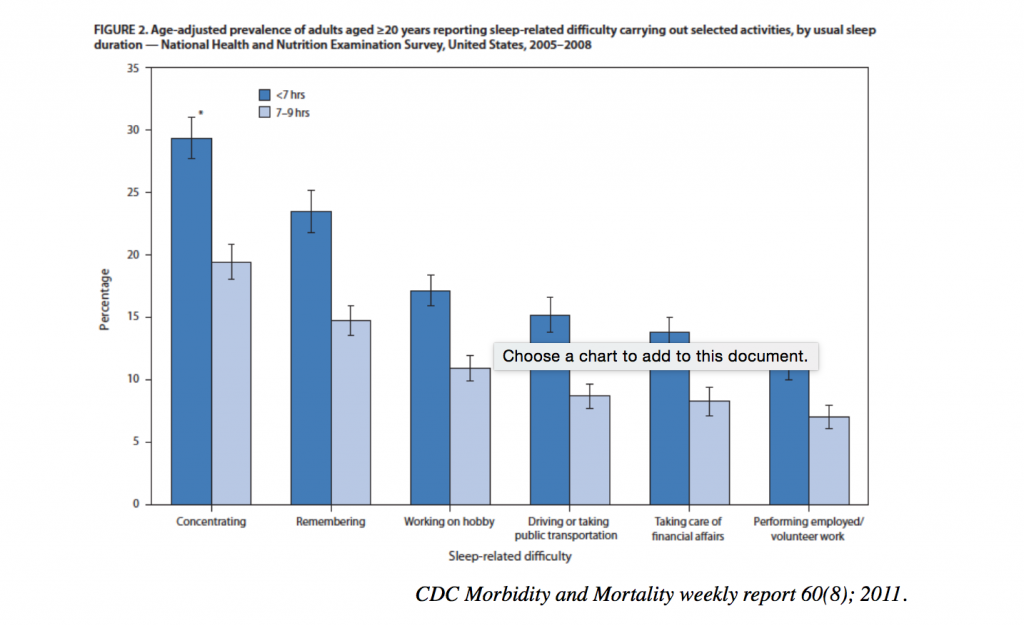

While individual needs may vary, it is generally accepted that adults require 7-9h of sleep per 24h period5. A reported 35% of adults in the US report less than 7 hours/night of sleep, and 28% report frequent insufficient sleep1. The acute effects of sleep deprivation include impaired mental and physical function (figure 1.). The changes in concentration and efficacy that you probably notice when you don’t get a good night’s sleep.

In addition to these functional effects that we are aware of, a number of other processes occur during sleep that are important to our overall health, including immune function regulation, hormone secretions responsible for growth, repair, and even appetite. Chronic and cumulative sleep deprivation, defined as less than 7h/night for more than 14 days out of 301, are associated with increased risk of illnesses including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, obesity, and depression2,3. In fact, 3-5% of obesity can be attributed to sleep insufficiency2 – and while that may seem insignificant, consider that that is independent of any dietary, physical activity, or other metabolically related variable.

Why Is Sleep So Important?

Are its benefits just a function of allowing our brains and bodies much needed respite from the activities and demands of the day? Or is it an active process in and of itself?

Are its benefits just a function of allowing our brains and bodies much needed respite from the activities and demands of the day? Or is it an active process in and of itself?

There’s a reason that our body wants to sleep when it’s dark and wake when it’s light, which have to do with circadian rhythms and hormone release. Many of the hormones responsible for processes from metabolism and appetite to cellular growth and repair are released from the brain in a cyclic pattern that follows that of the sun – our circadian rhythms. When sleep is cut short or not paired with environmental light/dark cycles, this can wreak havoc on the processes that those hormones regulate. Sleep deficiencies and disorders may therefore contribute to obesity, impaired immune function and infection, wound or injury healing, in addition to the many other functions that a rested brain and body are required for.

Further, not all sleep is created equal. Different types of sleep, as indicated by different types of brain waves measured on an EEG, have a respective roles in rest, repair, and function of the body and the brain.

The timing of these types of sleep are important and contribute to our overall quality of sleep – are we resting and repairing to optimize function? For example, slow wave sleep (SWS) happens more in the first half of the night. SWS is critical for the release of hormones, as well as for clearing wastes of the brain cells themselves. Brain cells don’t have blood supply like the rest of the body’s cells, so the removal of wastes is less constant during wakefulness. Our brain is only 2% of our body mass but uses up to 25% of our daily energy – so it’s swinging well above its weight class. But with energy use comes by-products and wastes of metabolism, that can impair brain function (consider how snappy and clear your brain is at the end of a long day – i.e. neither snappy, nor clear.). During SWS, brain cells can shrink up to 60% allowing the cerebral spinal fluid that the brain sits in to wash over cells, clearing metabolic wastes the accumulate throughout the day.

This process is essential for mental function including concentration, memory formation, problem solving, and creativity but also for coping with stress and emotional regulation.

REM Sleep

During the latter half of the night, REM sleep is more common. This is when dreams happen but also when short term memories learned throughout the day are converted into long-term memory. Neural networks are formed allowing you to consolidate the information taken in during the day. If you’ve ever found yourself dreaming about the things you were working on that day, this is a clear example of how your brain is anything but off when you’re asleep.

This series will explore the relationship between sleep and health and how exercise effects health through changes in sleep quality as an active process.

Related Article: 7 Tips To Get You Sleeping Again

References:

1. Institute of Medicine. Sleep disorders and sleep deprivation: an unmet public health problem. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2006.

2. Buxton OM, Marcelli E. Short and long sleep are positively associated with obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease among adults in the United States. Soc Sci Med 2010;71:1027–36.

3. Strine TW, Chapman DP. Associations of frequent sleep insufficiency with health-related quality of life and health behaviors. Sleep Med 2005;6:23–7.

4. CDC. Perceived insufficient rest or sleep among adults—United States, 2008. MMWR 2009;58:1175–9.

5. National Sleep Foundation. How much sleep do we really need? Washington, DC: National Sleep Foundation; 2010. Available at http://www.sleepfoundation.org/article/how-sleep-works/how-much-sleep-do-we-really-need. Accessed February 22, 2011.

You Might Like: