Exercise Treatment For Post-Concussion Syndrome

Catherine O’Brien

As discussed last week, Post-Concussion Syndrome (PCS) is marked by a series of persistent cognitive, psychological and physical symptoms following a concussion. There is some variance in the definition for PCS and there is a lack of consensus regarding the length of symptom presentation needed to diagnose PCS. While the Diagnostic and Statistics Manual and the World Health Organization do not provide the exact same definition for PCS, it is clear that persistence of cognitive, psychological and physical symptoms following a concussion is accepted and acknowledged to be a serious matter.

Related Article: Post-Concussion Management

Exercise As A Potential Treatment?

Typical treatment of post-concussion syndrome involves a combination of rest, education, medication and therapy. Athletes are encouraged to gradually increase intensity of exercise when returning to a sport post-concussion. In athletes and non-athletes alike, rest is necessary in the beginning phases of recovery and engaging in physical exercise or other physically demanding tasks too soon can increase risk for further damage.

At a certain point, however, Leddy et al. (2007, 2010) point out that exercise may be helpful in treatment planning as complete cessation of physical activity can have adverse effects in recovery including depression, fatigue and physiological deconditioning.

Given the positive neurological and psychological effects associated with exercise, it is not surprising that research has delved into the possibility of aerobic exercise to be used as a supplemental treatment for PCS. We know that aerobic exercise has been shown to improve cognitive performance and is associated with enhanced Brain Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF), which promotes neuronal development, recovery and protection.

Previous Research

Previous research indicates that while engaging in aerobic exercise too soon after a TBI has detrimental effects in terms of recovery, aerobic exercise 2 to 3 weeks post injury has the potential to upregulate BDNF in individuals with PCS.

Fortunately, there is some research focusing on the use of aerobic exercise as a treatment for post-concussion syndrome. Leddy et al. (2010) examined the safety and efficacy of exercise in the recovery period for patients dealing with PCS. They hypothesized that sub symptom threshold exercise training (SSTET) would reduce symptoms associated with PCS “by restoring autonomic balance and improving cerebral autoregulation and that there would be a relationship between improved exercise capacity and symptom reduction” (Leddy, 2010, p.22).

The Study

Participants were individuals from the Buffalo Concussion Clinic who met the criteria for PCS and who had been experiencing symptoms for at least 6 weeks (but not more than 52 weeks) and whose symptoms were exacerbated by exercise on a treadmill.

In order to test symptom exacerbation, participants underwent treadmill tests in which the machine was set to a speed of 3.3 mph and an incline of 0%. Each minute, the incline was increased by 1% and the speed was kept the same. Subjects rated exertion levels on a Borg scale and researchers took heart rate readings every minute. Once the subject indicated an exacerbation of symptoms, the treadmill was stopped.

Subjects completed this baseline treadmill assessment twice. The second treadmill test was administered 2-3 weeks after the first one. Once the subjects completed both of the initial baseline tests, the intervention began. Subjects were instructed to engage in physical exercise for the same duration as their treadmill test but were instructed to maintain 80% of their maximum treadmill heart rate as this was identified as sub symptom threshold heart rate. Participants maintained this program for 5-6 days per week and were instructed to always have another person present in the event they experienced dizziness, illness etc.

Participants were tested every three weeks until the treadmill exercise no longer exacerbated their symptoms.

The Results

Results demonstrated that there was indeed a reduction in symptoms associated with subsymptom threshold exercise treatment (SSTET) such that SSTET effectively and safely reduced symptoms of PCS.

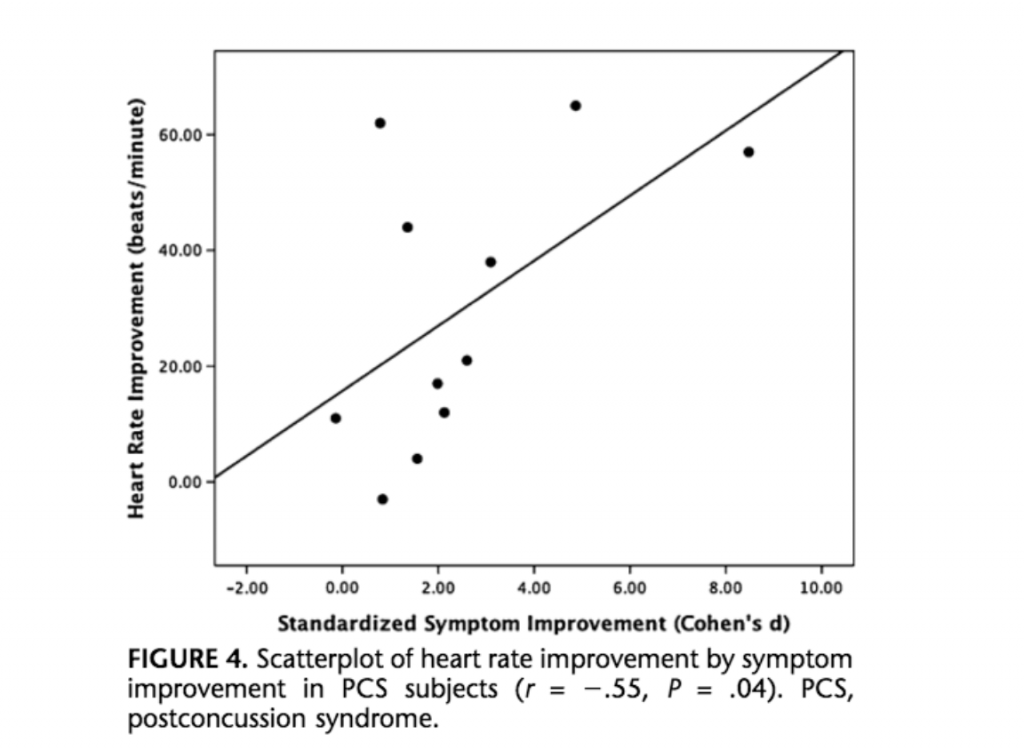

Now if you are like me, you may be wondering if the improvement in condition was simply due to the passage of time. Leddy et al. address this point in the discussion. Researchers gathered reports of participant symptoms during the 2 to 3 weeks prior to the intervention. Participants indicated being symptomatic at rest and did not show symptom improvement during this 2-3week period in which they were just reporting symptoms and not exercising. As such, Leddy et al. make the claim that the intervention was the primary cause of the improvement and not merely the passage of time. Additionally, as pictured below, there was a statistically significant correlation between heart rate improvement and symptom improvement.

These results provide some interesting insight and support the need for further investigation into aerobic exercise as treatment for PCS. Of course, each concussion should be treated individually and what works for one patient may not work for another. As such, these results should not be taken to suggest that aerobic exercise is a blanket treatment for all concussions but rather as an area of research to further pursue.

Related Article: 4 Key Risk Factors For Concussions

References:

Leddy, J.J., Kozlowski, K., Donnelly, J.P., Pendergast, D.R., Epstein, L.H., and Willer, B. (2010). A preliminary study of subsymptom threshold exercise training for refractory post-concussion syndrome. Clinical Journal of Sport Medecine, 20(1), 21-27.

Leddy, J.J., Sandhu, H., Sodhi, V., Baker, J.G., and Willer, B. (2012). Rehabilitation of concussion and post-concussion syndrome. Sports Health, 4(2), 147-154.

Leddy, J.J., Kozlowski, K., Fung, M., Pendergast, D.R., and Willer, B. (2007). Regulatory and autoregulatory physiological dysfunction as a primary characteristic of post-concussion syndrome: Implications for treatment. NeuroRehabilitation, 22, 199-205.

You Might Like: