What is a High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) Workout Anyway?

Evan Stevens

High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) is a huge ‘hit’ with exercise researchers and the general population alike. It is less time consuming and can imbue the same if not more benefits as traditional exercises like your long run, your laps in the pool, or your bike ride with your friends on the weekends. Indeed, as the growing body of evidence supporting HIIT and its many health benefits (one just needs to look through the excellent articles posted here at Forever Fit Science to see the good that HIIT can do) continues to add up, more and more people are switching to HIIT type workouts for themselves or as part as their exercise routines. While it is an admirable choice to switch things up and add HIIT to your lifestyle, there is one glaring problem that a lot of us face: a lot of us simply don’t know what a HIIT workout is.

High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) is a huge ‘hit’ with exercise researchers and the general population alike. It is less time consuming and can imbue the same if not more benefits as traditional exercises like your long run, your laps in the pool, or your bike ride with your friends on the weekends. Indeed, as the growing body of evidence supporting HIIT and its many health benefits (one just needs to look through the excellent articles posted here at Forever Fit Science to see the good that HIIT can do) continues to add up, more and more people are switching to HIIT type workouts for themselves or as part as their exercise routines. While it is an admirable choice to switch things up and add HIIT to your lifestyle, there is one glaring problem that a lot of us face: a lot of us simply don’t know what a HIIT workout is.

Related Article: How HIIT Changes Our Body

What Is HIIT?

One of the biggest points of confusion is that most of us don’t actually know what HIIT is, let alone how to properly do a workout. That’s in part due to the fact that HIIT itself doesn’t really have a true, set in stone definition.

Scientists use HIIT and interval type training to define a number of different exercise protocols ranging in length and rest period, whereas in popular culture we’ve taken it to mean something similar but different too. One of the most important things that we should note is that HIIT is an aerobic workout. Many people still firmly believe that it is anaerobic as it is short(ish) burst of intense exercise. We know physiologically that working at certain thresholds and intensities puts us into the anaerobic zone.

However, we also know that the anaerobic system is finite and that we eventually have to go aerobic to do the work we need to over a number of intervals. Realistically you will use your anaerobic system for the first interval or two of your HIIT workout. But beyond that, to maintain your ability to exercise you will go aerobic. That is because your anaerobic system is really only good for 30 seconds or so (with training it can get better but it still will not sustain you for an entire workout). This brings us to one of the major points of contention that a lot of people have – how long are the actual intervals of a high-intensity interval workout?

What Constitutes HIIT?

Reading through the literature it is difficult to pinpoint what constitutes HIIT. There are many different regimens used in scientific models and studies that all use different protocols to qualify the work done as HIIT exercises.

- Coe Regimen: repeated (10-12) 200m sprints at or near max speed, 30s (seconds) full rest.

- Tabata Regimen: repeated bouts of 20s ultra-intense exercise (170% VO2 Max) with 10 seconds rest for 4 minutes.

- Gibala Regimen: 3-minute warm-up, 60s intense exercise (95% VO2max) followed by 75 seconds rest, repeated 8 -12 times.

- Zuniga Regimen: 30s at 90% VO2max followed by 30 seconds easy rest, repeated until failure.

- Vollaard Regimen: 10 minutes of easy cycling interspersed with two bouts of all-out cycling for 20s.

There are many more protocols and regimens out there, with some exercise bouts ranging in duration from 15 seconds up to as long as three minutes, and even the above regimens have variations within them too. But this still doesn’t give us great insight as to what we should be doing ourselves for a HIIT workout.

Related Article: 7 HIIT Medicine Ball Exercises

Why HIIT Workouts?

While many scientific regimens exist, a large meta-analysis of all the different regimens showed that there isn’t much difference between them in terms of physiological and health outcomes. The intermittent nature of the regimens, periods of short, intense exercise followed by short rest, all has beneficial effects on metabolism, muscle strength, bone health, memory, and brain function. Beyond that though, HIIT offers a short, reliable way to go into an excess post-exercise oxygen consumption state (EPOC). Also known as oxygen debt, EPOC is the amount of oxygen required to restore your body to normal, resting metabolic function. Being in EPOC creates a small, but a significant effect that essentially burns calories even after you’ve concluded your workout, a post-exercise burn and may be why HIIT’s effects on metabolism last longer than some traditional type exercises.

Effort Matters

Getting into the EPOC zone is where we run into trouble, however. It requires us to work hard. While there is still a lot of debate over what constitutes a HIIT workout, most evidence suggests that you can’t go wrong with any of the regimens. However, they only work if you are prepared to really work hard. HIIT workouts require you to be working at least at 85-90% of your maximum effort. That is easier said than done as it is natural for us to try and take it easy.

An interesting study released by a team at Ball State presented at the American College of Sports Medicine Conference discussed how even when we are instructed to go hard or easy, seem to have trouble doing so. The study followed collegiate track athletes over a few training sessions and charted their perceived effort versus their expected effort. On the athlete’s easy days, their coaches told them their effort should be a 1.5 out of a possible 10 and on their hard training day, the effort should be an 8.4, which is right around where you would want to be in a HIIT type workout. However, the athletes reported that their easy days averaged as a 3.4 and their hard days were just a 6.2. These are highly trained collegiate athletes and even they had trouble pushing themselves to go at the prescribed work threshold. This is the biggest hang-up for HIIT workouts – most of us simply do not go hard enough.

Find Your VO2max

Many of us don’t know what our VO2max is so it is difficult to know just how hard we are/should be going. One way to get around this is by using Heart Rate Monitors. Heart rate monitors are great beginner tool to get used to knowing what your optimal HIIT workout zone is. There is a lot of variability within heart rates zones, depending on current health and fitness status and individual variability, but even using general training guides as a base can be a good start. For example, if you are 60 years old, have a resting heart rate of 60 and max heart rate of 170, then you should aim to workout at a heart rate around 145-150 (85-90% max heart rate). The caveat being, you need to know your maximum heart rate in the first place; however, most age-heart rate guides (often found on a dimly-lit wall in your local gym) will give you a good approximation if you are unsure right away. Just be aware that as you get stronger and get more fit, the numbers change and may need to change your heart rate zones to accommodate your newly formed fitness.

Related Article: Get in the Zone: Heart Rate Monitoring

Beginner HIIT Workouts

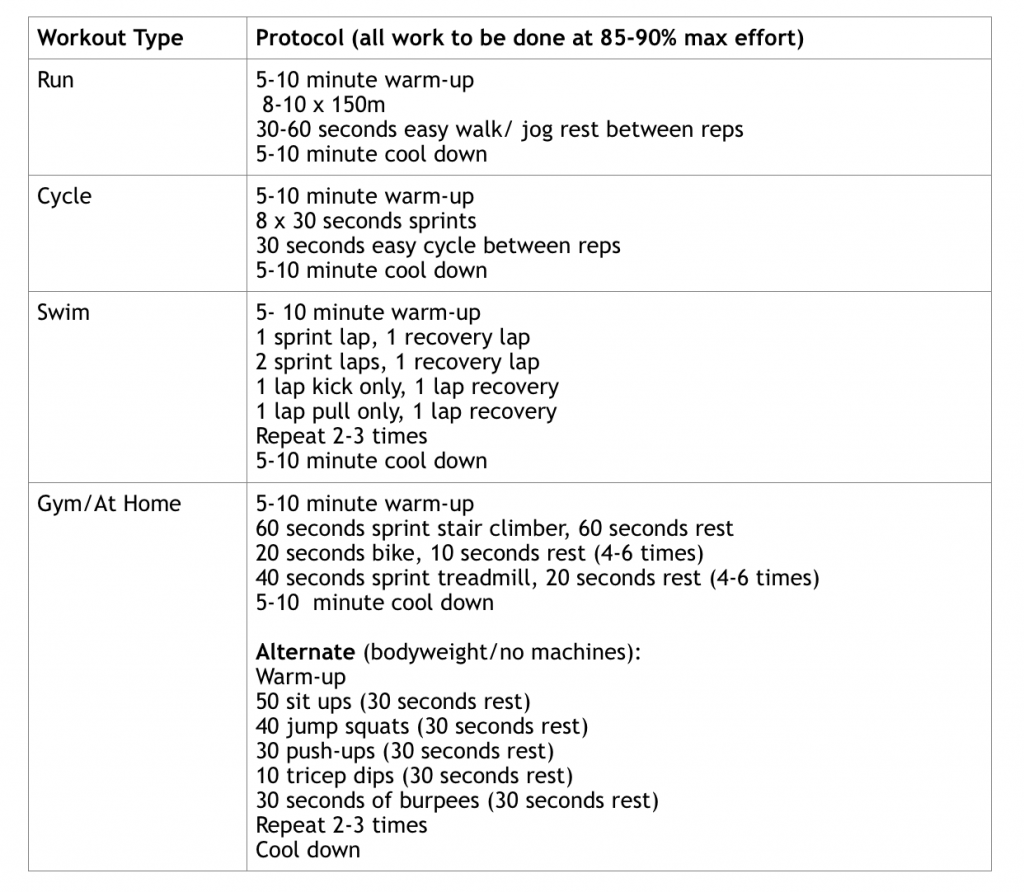

So, you’ve figured out where you are and your training zones. You know the effort you need to be working out at to benefit most from HIIT workouts and are ready to actually try some workouts for yourself. Below are some different workouts, depending on your workout preference, you can do on your own (although it is always better with a friend).

HIIT When You’re Fit

As you get more fit and your ability to workout improves, the aforementioned workouts may become too easy and your fitness goals may change as well. Instead of general fitness, you may start to actually want to work on performance to improve something specifically. Then you get into specific workouts for your events, and you have to vary the workouts a little more; intervals of varying lengths, changing the rest protocols to upset your body’s expected rest cycle, or adding strength or alternate training methods by adding different strength exercises on top of your current training can all help to keep you focused and improving. This means your workouts get a little longer and maybe you have to do some off-day longer stuff to keep the strength up. If your goal is just to maintain fitness maybe consider adding 15 seconds to intervals or go for additional reps or sets. You just have to remember that your effort has to remain above 85% to really get the most benefit.

It leaves the “so what’s next” question unanswered. But here’s the thing, what’s next is up to you. If you think you’ve reached a point where you think the basic workouts are getting too easy, it is up to you to decide what you want to do next. Some options include:

- Add more intervals.

- Cut the rest from your workouts.

- If you enjoy specific types of workouts (running or swimming or cycling), think about joining a local club or team. They will offer additional training with a group that is gear towards your specific goals. Talk to a coach or someone with some knowledge in the sport. If it is something you really enjoy, pursue it.

- If you enjoy the gym most, try switching from body weights to machines, or from machines to free weights (dumbbells and barbells) for your workouts to stress your system more and work on movement and balance.

- Keep pushing yourself hard.

- Keep it fun!

Related Article: 6 Tips to Fuel Your HIIT Nutrition Plan

Citations

Judge, L., Links, B., Mullally, A., King, M., Waterson, Z. and Bellar, D. (2018). Comparing Training Load and Intensity Perceptions Between Female Distance Runners and Their Coach. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 50, p.179.

Seiler, S. (2010). What is Best Practice for Training Intensity and Duration Distribution in Endurance Athletes?. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 5(3), pp.276-291.

You Might Like: