How Hydration Affects Short Endurance Performance

Hunter Bennett

Staying adequately hydrated has long been considered one of the most important aspects of sports nutrition. This does seem logical if you think about it.

We know that the human body is made up of around 70 percent water. We also know that during prolonged periods of dehydration, you will see changes at a cellular level that can result in impaired health and declines in both cognitive and physical function.

However, there is some recent research suggesting that in certain sporting scenarios, the loss of hydration is so minimal, that we don’t have to worry about it at all. This is namely in exercise that lasts less than 90 minutes.

Which is an interesting viewpoint, and one that we want to dive into in further detail.

Hydration and sports

Over the last few years, we have seen some serious debates within the world of research. This research examines the most useful fluid intake strategies that athletes can employ to maximize their performance.

It was initially hypothesized that a decline in hydration status would result in a sharp reduction in cardiovascular function and efficiency, which would subsequently cause a decrease in physical performance.

With this in mind, the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) has developed guidelines that suggest that athletes should drink enough water to ensure they lose no more than 2% of their body mass as fluid during exercise performance (Sawka, 2007).

Now, there is indeed some research that shows that a decline in hydration status of more than 2% of your body weight can cause some slight alterations in cardiovascular function, power output, and even an increase thermal temperature (Dion, 2013).

However, this does not appear to have impact performance outcomes in any way.

In fact, it has even been shown that you can afford to lose up to a whopping 4% of your body weight through fluid loss before it has any negative implications on your endurance performance (Goulet, 2014).

Which really makes you wonder – for shorter endurance events where you are unlikely to lose that much fluid, is drinking water necessary?

Particularly when we consider the fact that maintaining hydration during a race (whether it be by carrying a drink bottle or collecting drinks at hydration stations) may inhibit running economy and physically slow you down.

Food for thought, at the very least…

Related Article: Water and Hydration

What is the recommend daily hydration for athletes?

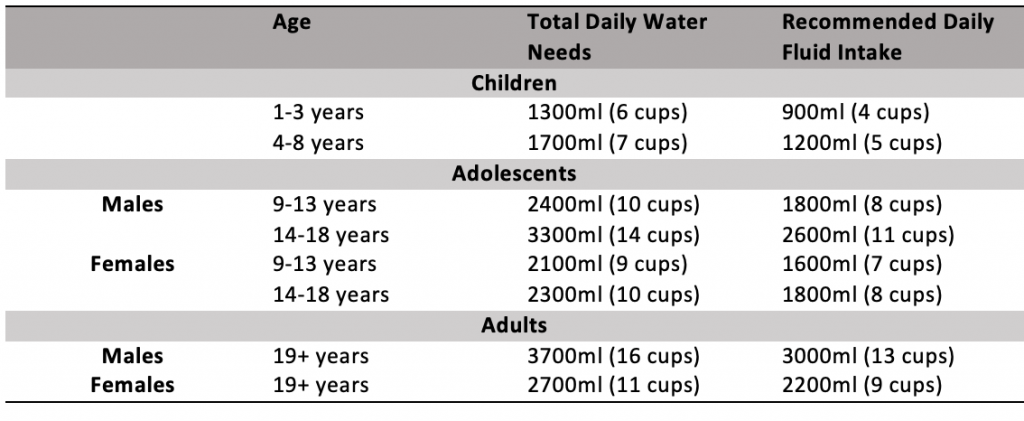

It is quite fortunate that the Institute of Medicine (IOM) has gone ahead and created a thorough set of guidelines that outline the optimal daily water intake for humans (Riebl, 2013).

While these guidelines don’t distinguish between athletes and non-athletes, they provide a baseline indication of how much water you need to be consuming on a daily basis to maintain optimal health and function.

These recommendations are as follows:

Looking at the above table, I realize that you might be interested to know as to why there is a slight disparity between how much water you need, and your recommended intake. This is because a lot of the food you eat contains water.

As a result, you only need to drink enough water to supplement the fluid found within the food you eat.

So, if we consider these numbers a baseline level of hydration that all athletes need to achieve, it begs the question – ‘as someone who trains a lot, how much water should I drink?’ – and to be honest, it depends.

Individual Variance

You see, during exercise and training, the rate at which you lose fluid is extremely individual. Some people lose a lot, while others will lose hardly any at all. This means that your daily fluid intake should really match up with your daily fluid loss.

While this may sound quite complex to work out, its actually not, because your body does it for you!

You have evolved to have an incredibly sensitive network of physiological controls that maintain both body water and fluid intake through your thirst reflex (Popkin, 2010).

Via an extensive network of nerves and cells, even a mild fluid deficiency will be picked up by the physiological control system within your body and stimulate what is known as the reactive (or physiological) thirst reflex.

Your body will literally tell you when it needs more water, and when you can stop drinking.

Hydration during short endurance performance

During short endurance bouts that last 90 minutes or less, you can expect to see a loss of fluid that corresponds with approximately 2% of your body weight. As we now know, this does not appear to impact physical performance.

Subsequently, if most of your events last less than this time frame, you may not need to worry about maintaining hydration during your event at all.

However, there are a couple of caveats around this.

First and foremost, you want to make sure that you pre-exercise hydration is on point. For most people, this means making sure that you have achieved your recommended daily fluid intake every day for the week leading up to the event, and ideally the day of the event.

Secondly, you want to make sure that you consume 2-3% of your body weight in water after the event has been completed. By making sure that your post-exercise hydration is solid, you can enhance recovery and ensure health is maintained at optimal levels after the completion of the race.

Hydration during long endurance performance

Alternatively, during any events that run longer than 90 minutes, you do run a risk of getting close to losing 4% of your body weight through fluid loss. As we have already discussed, this can impact your performance.

As a result, maintaining hydration during the race is going to hold more importance in this scenario.

You can manage this effectively by aiming to consume somewhere between 150 and 250mls of fluid every 15-25 minutes during exercise (this is obviously dependant on your size). This has been shown to offer an acceptable method of maintaining hydration status during exercise (Backes, 2016).

Obviously, as with short endurance performance, you want to make sure that both your pre-exercise hydration and post-exercise hydration strategies are also on point.

Are there any water alternatives?

With all this talk of water intake, I thought it would be beneficial to touch on two common alternatives to water intake that have been appearing within the literature (and within competition) with an increasing incidence.

- Mouth rinsing

- Sports drinks

Each of these has been suggested to offer an alternative to water that can stave off hydration and improve performance – but is this really the case?

Water ingestion vs a simple mouth rinse

There is some evidence to suggest that during shorter endurance activities, simply rinsing your mouth with water at regular intervals may be more than enough to stave off thirst and maintain performance (Shaver, 2018).

A recent study compared the effects of a simple mouth rinse (every 3km) against consuming 355ml of water during a 15km time trial. The results were pretty interesting!

First, the mouth rinse group actually lost less fluid through sweat than the drinking group. Moreover, there was absolutely no difference in their performance outcomes. There was also no difference in how difficult they perceived their exercise to be.

Now, you might be wondering what the benefits are if you opt for a mouth rinse over an actual drink, given that the performance outcomes are the same.

Well, carrying a single, smaller fluid container (rather than a larger drink bottle) will reduce the amount of load carried by a small amount, which may enhance performance. Additionally, some athletes have been shown to experience some gastrointestinal discomfort during exercise when consuming water. Consuming a smaller amount of water is a very easy remedy for that.

Related Article: Effects of Dehydration on Athletic Performance

Water vs sports drinks

We have already mentioned that severe fluid loss (4% or more) as a result of sweating can cause declines in performance.

But what we didn’t mention was that through this process of sweating, the body also loses the key electrolyte sodium. The excessive loss of sodium has been suggested to speed up this decline in performance (Ayotte, 2018).

To remedy this, the consumption of sports drinks during exercise has become an increasingly common method to replace the fluid and electrolytes lost through sweat.

Interestingly, it appears that during shorter duration endurance exercise performance (less than 90 minutes in length) the consumption of sports drinks offers no benefit over water on performance outcomes (Briars, 2017).

In fact, sodium loss does not appear to inhibit performance until exercise has lasted for around three hours!

As such, the supplementation of higher sodium sports drinks (or even salt capsules as an alternative) may be necessary for those athletes who participate in long endurance performance (that lasts 3 hours or more), in order to maintain serum electrolyte concentrations and maximize performance.

But they may not be necessary for events lasting less than that duration.

Take Home Message

Staying hydrated is essential for the maintenance of health and function on a daily basis. However, for shorter endurance events, it appears that maintaining hydration throughout the event will not actually improve performance in any manner.

So, if you keep yourself well hydrated in the lead up to the event, you can ditch the bottle and focus solely on your event.

References

Sawka, Michael N., et al. “American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Exercise and fluid replacement.”. Medicine and science in sports and exercise 39.2 (2007): 377-390.

Dion, Tommy, et al. “Half-marathon running performance is not improved by a rate of fluid intake above that dictated. By thirst sensation in trained distance runners.”. European journal of applied physiology 113.12 (2013): 3011-3020.

Goulet, Eric DB. “Effect of exercise-induced dehydration on time-trial exercise performance: a meta-analysis.” Br J Sports Med 45.14 (2011): 1149-1156.

Riebl, Shaun K., and Brenda M. Davy. “The hydration equation: update on water balance and cognitive performance.” ACSM’s health & fitness journal 17.6 (2013): 21.

Popkin, Barry M., Kristen E. D’Anci, and Irwin H. Rosenberg. “Water, hydration, and health.” Nutrition reviews 68.8 (2010): 439-458.

Backes, T. P., and K. Fitzgerald. “Fluid consumption, exercise, and cognitive performance.” Biology of sport 33.3 (2016): 291.

Shaver, L, N., et al. “No Performance or Affective Advantage of Drinking versus Rinsing with Water during a 15-km Running Session in Female Runners.”. International journal of exercise science 11.2 (2018): 910.

Ayotte, David, and Michael P. Corcoran. “Individualized hydration plans improve performance outcomes for collegiate athletes engaging in in-season training.”. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition 15.1 (2018): 27.

Briars, Graham L., et al. “Swim drink study: a randomized controlled trial of during-exercise rehydration and swimming performance.” BMJ pediatrics open 1.1 (2017).

You Might Like: