Fat, Carbs, Protein and Recovery. Is There A Silver Bullet?

Evan Stevens

The first talk in this session was very similar to the talks that made up the first GSSI nutrition talk. Namely, they explored how the major macronutrients can be used in various amounts to maximize training and promote exercise recovery. The main theme, however, was that we need to account for the individual and the sport rather than a clear-cut description of what we should eat and how we should train. Each athlete is different and performs their different sports in an individual manner.

There is no “silver bullet” to nutrition and maximizing performance. What we do know is that carbohydrates are the most important factor for performance, protein is best for recovery, and fat really isn’t that useful for performance. Even when athletes periodize their training, going weeks at high fat and then a week or two before a big competition introducing more CHOs (thinking that they would be “fat adapted”) performed poorer than those who trained at adequate levels of CHOs through their entire training period.

In fact, when researchers tested this on trained race walkers (top 50 IAAF ranked athletes), they found that although there was a slight increase in VO2 Max, the walker’s performance dipped well below IAAF standard ranking. They also developed rashes and irritability, and all athletes said they would never train or perform on a high fat diet ever again. This reiterated the point made in the first GSSI session. The harder we work, the greater the reliance on CHOs. Blood flow does not go to where the fat is stored and is instead diverted to the working muscles. This makes stored fat essentially a waste of energy (and space).

Take Away

Contrary to what some media experts will have you believe, training on high fat, low CHO diets does not improve performance. In fact, high fat diets hinder performance. The energy that is stored in fat is inaccessible at higher efforts of exercise (above 60% VO2 Max).

Second Talk

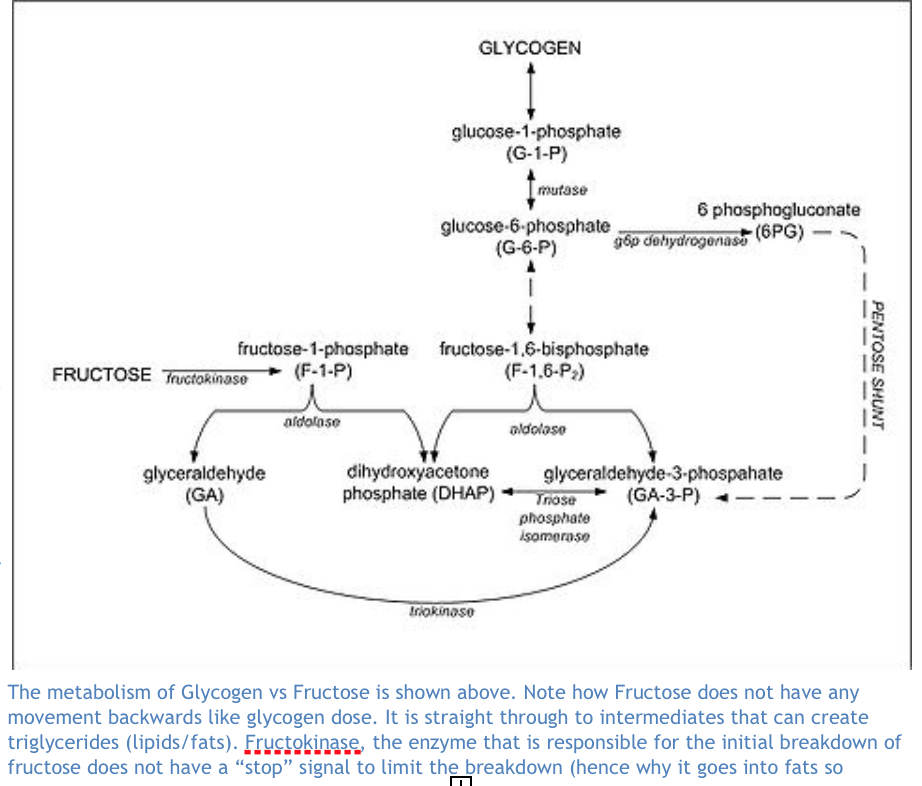

The second talk of this session was about fructose metabolism. By now I’m sure we are all familiar with fructose in one way or another. High fructose modified corn syrup is in most sweetened products and has come under blame for the increasing rates of obesity and diabetes in our western diets. Fructose, like glucose, is a monosaccharide (simple sugar) found most abundantly in fruit. However, glucose and fructose differ. Glucose is needed by all cells in the body, and production can be shut off and  energy can be stored in the form of glycogen.

energy can be stored in the form of glycogen.

Fructose, on the other hand, doesn’t seem to have a shut off. While it can be stored as glycogen, it is more often dumped into the blood (raising blood sugar levels causing insulin spikes). It is also converted very quickly into fat. Fructose seems to be able to increase circulating plasma triglycerides independent of additional energy intake (no additional calories, just fructose can lead to this increase).

Fructose is rapidly taken up by the liver. Because it is rapidly turned into triglycerides (lipids), this can lead to deposits of intrahepatic lipid deposition. Continual exposure can result in fatty liver disease in as little as a few days. What the researchers did add, however, was that exercise (even in small quantities) can totally mitigate the changes brought on by increased fructose consumption. Additionally, because it can skip parts of glucose’s break down steps in the cell and can be converted into stored energy very quickly (both fat and glycogen), it is the perfect source of CHOs to quickly restore glycogen reserves post-workout.

Fructose Take Away

Fructose is metabolized differently to glucose. It is very quickly digested and converted into stored energy (glycogen or lipid). Too much can cause fatty lipid disease in just a few days, when consumed during very sedentary periods. But because it is so quickly digested, it can be used to restore glycogen reserves very quickly post exercise.

Third Talk

The final talk was of this nutrition session was about athletes maximizing recovery and accelerating return to play. The speaker started by saying that injury leads to periods of disuse, which can result in anabolic resistance (the inability to build muscle). In fact, it takes as little as five days of total disuse to lose muscles that would have otherwise taken ten weeks to build. As well, during periods of disuse excess calories can further accelerate anabolic resistance (increasing the amount of protein to try and prevent muscle mass loss actually exacerbates the problem).

So, if immobilizing a limb can cause a decrease in muscle protein synthesis, what can we do to attenuate the problem? High doses of protein does not seem to do anything as the speaker showed several examples where 30g or more of protein still resulted in a loss of muscle protein mass, however, when given small doses of just leucine, the loss of muscle synthesis was slowed significantly (as we’ve heard from previous talks about the importance of leucine). Yet when subjected to as little as ten minutes a day of muscle contractions the loss of muscle was almost completely negligible.

It seems as though exercise is the key to preventing loss of muscle either from disuse or immobilization. The speaker then showed an interesting study where when one leg was immobilized and the other was worked, muscle loss in the immobilized leg was limited; it seems as though exercise in any part of the body can attenuate loss in other areas. When leucine supplementation was added, there was an even greater effect to preventing the loss of muscle.

Exercise Recovery Take Away

Exercise of any kind, even small contractions, can prevent muscle loss in injured parts of the body and speed recovery. When used in conjunction with leucine supplementation, muscle loss is almost negligible.

You Might Like: