Gender May Affect Exercise Motivation

Catherine O’Brien

There is a wealth of research on the role of motivation in exercise adherence and goal pursuit.

There is a wealth of research on the role of motivation in exercise adherence and goal pursuit.

According to the self-determination theory (Deci and Ryan, 2000) the underlying motivation for pursuing a goal is a good predictor in the outcome and success of that goal such that when motivation is autonomous, the goal is often met with more success than when the goal is controlled.

Research also points out the different ways women and men set and meet goals. For example, research discussed by Teixeria et al. (2012) demonstrated the presence of a negative association between externally regulated goals and physical exercise for men but not women. For women, however, there was a positive association between introjected motivation (motivation driven by self-approval) and exercise but such a relationship was less obvious among men. Based on the previous research on motivation, relationships and gender as they function in predicting exercise, Gore, Bowman, Grosse and Justice (2016) conducted research to examine the role of relational motivation in exercise across genders.

The Terms

Before diving into the details and methods of the study, there are some terms that need to be discussed. Gore et al. identify relationally-autonomous reasons in health behavior (RARHs) as a key term in this paper as their aim is ultimately to investigate the degree to which RARHs motivate health behavior like exercising.

A goal is said to be relationally-autonomous when it takes into account not only the goal-setter’s needs and values but also those of a close partner. In this way, RARHs is different than personally-autonomous goals (PARs) which focus solely on that of the goal setter. Relationally-autonomous motives are not to be confused with social support.

“When people articulate RARHs for their goals, they are describing why they pursue that goal, and these reasons involve the consideration of others’ interests as well as one’s own” (Gore et al. 2016, p.39).

Research also suggests that women tend to define themselves in terms of their relationships more so than men do and as such, set different types of goals (often more focused on relationships) and approach goals differently (desire the participation of others). Now that we have established an understanding of RARHs and some of the key differences in how men and women set goals, we can move on to the study.

The Study

Gore et al. predicted that the degree to which RARHs are associated with health related behaviors like exercise would be moderated by gender such than women would have a stronger positive association between RARHs and exercise compared to men.

The First Study

assessed the relationally-autonomous reasons for health related behaviors. Participants read and responded to a series of statements about why they eat healthy and exercise. Responses included both relationally autonomous reasons for health behavior like “because someone I’m close to thinks it is enjoyable” personally autonomous reasons like “because I really believe it is an important thing to do” and controlled responses “because I the situation demands it”. A series of analyses revealed no significant overlap between motive types and confirmed that the RARHs responses represented a distinct type of motive.

The Second Study

examined the relationship between relationally-autonomous reasons, body composition and fitness across gender. They used the same measure of RARHs as in the first portion of the study. Body composition was obtained through a series of measurements (height, weight, waist circumference, body fat measurement etc.) and fitness tests were administered (ex/ number of pushups participants could complete, grip strength etc.) to measure fitness level.

While overall men had greater fitness and better body composition, results indicated that women benefited more from relationally-autonomous reasons for health behaviors than men such that high levels of RARHs was associated with better body composition scores and higher fitness scores in women (see figures below).

The Third Study

introduced healthy eating habits as a measure and, similar to the results of study 2, results from study 3 demonstrated that RARHs predicted health behaviors for women. Gore et al. do acknowledge that, because the study was cross-sectional, it does not measure the impact of RARHs overtime. Because of this and the lack of manipulation in cross-sectional studies, the results do not account for external environmental factors that may predict RARHs.

The Fourth Study

Finally, study 4 examined the role of RARHs for health in a health program. They predicted that presence of a close exercise partner would promote the use of RARHs and that having relational reasons for health behavior would be associated with higher levels of success in a fitness program. Based on the findings from the previous study, they predicted that these effects would be more prominent for females.

Participants completed pretests online (Time 1) that addressed health motives, demographics, presence of an exercise partner etc. They were then asked to schedule two (Time 2 and Time 3) visits to the “Get Fit!” health program lab. Time 2 was a visit to the lab that included an informational session. At the end of this session participants were asked to keep track of what they ate and how much they exercised in a health log for the upcoming week. They were also asked whether they intended to engaged in healthy behavior during the coming week or not.

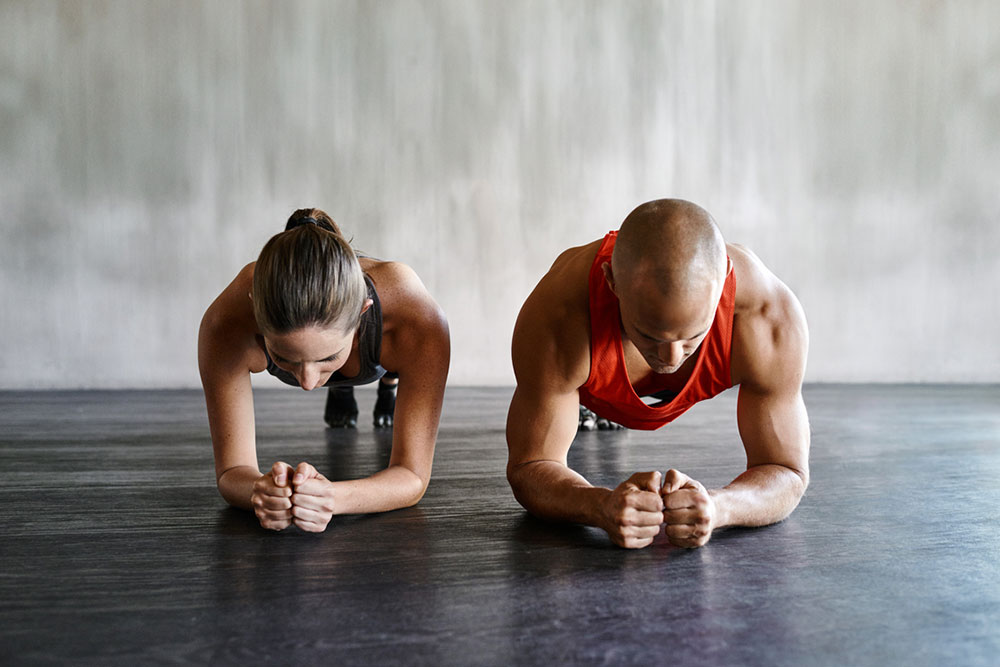

One week later, participants returned to the lab for their follow up (Time 3) in which their effort, progress and support from others during the past week were assessed. As expected, people who had someone close to them as an exercise partner had higher levels of relationally-autonomous reasons for health. When it came to utilizing RARHs in pursuit of health goals, however, there was a difference between men and women. Women with high levels of RARHs reported greater effort and progress at the follow up session compared to men.

Takeaway

So what do these results mean for you? Simply, this study makes a case for working out and eating healthfully with someone close to you. Results indicate that, for women especially, setting goals that are grounded in relationships and pursuing goals with a close other promote successful pursuit of a healthy lifestyle.

References

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The ‘what’ and ‘why’ of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11, 227–268.

Gore, J.S., Bowman, K, Grosse, C., and Justice, L. (2016). Let’s be healthy together: Relational motivation for physical health is more effective for women. Motivation Emotion, 40, 36-55.

Teixeira, P. J., Carrac ̧a, E. V., Markland, D., Silva, M. N., & Ryan, R. M. (2012). Exercise, physical activity, and self-determination theory: A systematic review. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 9, 78.

You Might Like: