Exercise To Feel, Think, and Act Like a Young Brain – Part 2

Author: Julia C. Basso, PhD

Affiliation: Post-doctoral Research Associate, Center for Neural Science, New York University

Exercise To Feel, Think, and Act Like a Young Brain – Part 2

Gretchen Reynolds, an exercise blogger for the New York Times, recently wrote a post entitled, “Does exercise help keep our brains young?” In it, she reported on recently published research by Dr. Hideaki Soya and his group at the Laboratory of Exercise Biochemistry and Neuroendocrinology at The University of Tsukuba in Japan. I recently visited the annual Society for Neuroscience meeting in Chicago, IL. During my visit, I got to talk to one of the members of Dr. Soya’s laboratory about this exciting research and some new findings in the laboratory. This research regards the effects of exercise on the brain of older individuals, which I am pleased to share with you here.

An Overview Of Aging Brains

When we have a young brain, it is highly efficient at processing cognitive demands. As we age, the brain recruits additional resources to perform these cognitive tasks. This idea comes from work done using techniques such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) or functional near infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS). With these techniques, scientists can view what is happening in the brain of individuals while they perform different cognitive tasks.

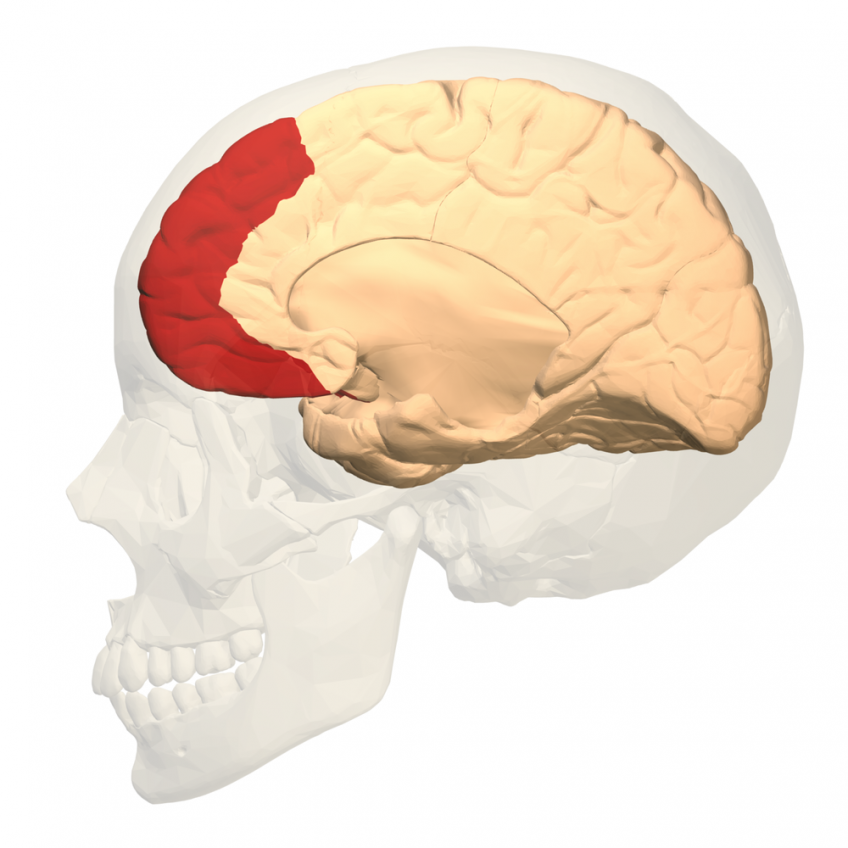

When we image the brain during tasks that involve the learning and remembering of certain information, an area of the brain known as the prefrontal cortex activates. In general, this area of the brain is involved in our executive functions such as short-term memory, attention, concentration, switching between tasks, and future planning. For young adults, only one side of the prefrontal cortex is needed to perform these tasks, a process called lateralization. However, inI older adults, the other side is recruited to help perform the task correctly. That is, the older brain is less efficient than the young brain. This phenomenon has been termed HAROLD for hemispheric asymmetry reduction in older adults (Cabeza, 2002).

A Fit, Older Brain

A collection of work shows that high-fit older adults out-perform their low-fit counterparts on a variety of tasks that depend on the prefrontal cortex (Hillman et al., 2008). Thus, it appears that at least at a behavioral level, staying fit helps to keep the brain healthy and performing at levels similar to younger adults. The brain mechanisms underlying these exercise-induced improvements in cognition, however, are still unknown. Therefore, Dr. Soya and colleagues set out to determine if the brains of high-fit older adults act like the brains of young adults while performing cognitive tasks.

60 older men (70.3±3.2 years of age) underwent fitness testing. They performed the Stroop Test while having their brains imaged using fNIRS (Hyodo et al., 2016). This imaging technique takes advantage of the fact that oxygenated blood flows to utilized areas of the brain By emitting near infrared light, this machine is able to detect the amount of blood flow or activity in specific brain regions. The cognitive task that these individuals performed was a test of attention and response inhibition. In other words: the ability to suppress an unwanted response, executive functions that rely upon the prefrontal cortex.

Testing

Testing

For the test, participants had to indicate whether the color of either ‘XXXX’ (neutral condition) or the words ‘RED’, ‘GREEN’, ‘BLUE’, or ‘YELLOW’ were printed in the same or different color as another color word presented in black ink. In some instances, the word (or ‘XXXX’) and the color of the word matched (congruent), but in other instances, they did not (incongruent). The incongruent trials are much more difficult because you need to inhibit your response to read the word and instead state the color. This delay in response time is called the Stroop interference effect (Laird et al., 2005) and is a decision-making process that declines with age (See & Ryan, 1995)

Results

The author’s revealed several things. First, they confirmed the HAROLD phenomenon in this group of older men. While performing the Stroop Test, subjects showed equal activation of both the right and left hemispheres of the prefrontal cortex. However, they found that individuals who performed the task better (i.e., showed a faster Stroop interference effect) showed greater activation in the left prefrontal cortex. That is, participants who were more cognitively intact showed a decrease in the HAROLD phenomenon. Who were these individuals? Men who were more physically fit performed better on both the Stroop Test and presented greater levels of activation in the left prefrontal cortex.

Additional analyses revealed that the lateralized brain activity may actually underlie the association between fitness and cognition. Collectively, this work indicates that in older individuals, a more fit brain shows similar patterns of activity and performs at similar behavioral levels to younger adults. Future work is needed to see if this relationship holds true for older women. Moreover, a more direct comparison could be made between young and old brains if similar studies were conducted using a wider range of age groups.

Effects of Mild Exercise

More recent work in Dr. Soya’s laboratory, presented at the 2015 Society for Neuroscience Conference and led by Kyeongho Byun, examined the effects of a single bout of mild exercise on both cognitive performance and brain activation (Byun et al., 2015). Healthy, male and female older adults (68.7±1 years of age) performed a mood assessment and the same Stroop Test described above while having their brain activity recorded with fNIRS both before and after a period of either 1). 15 minutes of rest or 2). 10 minutes of low-intensity cycling and then 5 minutes of rest.

The acute exercise intervention enhanced mood (positive arousal) and cognition (Stroop interference effect) as well as increased activity in the prefrontal cortex. Further, the level of brain activity positively correlated to improvements in mood and cognition. These findings were very similar to an earlier report of the same work in young adults (Byun et al., 2014). It suggested, “regardless of age, mild exercise has beneficial effects on executive function.” The prefrontal cortex supposedly mediates this function.

Conclusions

Together, this work tells us that exercise helps the aging brain function like a young brain. Essentially, exercise serves as a fountain of youth. It helps us feel (mood), think (cognition), and look (brain activity) younger. Additionally, the more you exercise and increase your fitness level, the more you can gain in terms of achieving that healthy, young brain. The first study was cross-sectional in nature (i.e., did not include an intervention) and the second study utilized a low-intensity exercise regimen.

Therefore, we need future work in elderly individuals in order to determine whether acute or long-term training with maximal exercise regimens such as high-intensity interval training (HIIT) lead to even greater brain benefits. What is the best exercise strategy to push the aging brain to achieve youthful patterns of activity? Considering the positive correlations between fitness level (VO2 max), cognition, and brain activity, I hypothesize that an exercise regimen like HIIT, which optimizes VO2 max gains, would be ideal in realizing optimal brain health in the elderly.

References:

Byun, K., Kazuki, H., Kazuya, S., Genta, O., & Soya, H. (2015). Acute mild exercise boosts executive performance in older adults by eliciting positive-arousal-related prefrontal activations: an fNIRS study. Presented at the annual Society for Neuroscience Meeting, Chicago, IL.

Byun, K., Hyodo, K., Suwabe, K., Ochi, G., Sakairi, Y., Kato, M., … & Soya, H. (2014). Positive effect of acute mild exercise on executive function via arousal-related prefrontal activations: An fNIRS study. Neuroimage, 98, 336-345.

Cabeza, R., Anderson, N. D., Locantore, J. K., & McIntosh, A. R. (2002). Aging gracefully: compensatory brain activity in high-performing older adults.Neuroimage, 17(3), 1394-1402.

Hillman, C. H., Erickson, K. I., & Kramer, A. F. (2008). Be smart, exercise your heart: exercise effects on brain and cognition. Nature reviews neuroscience, 9(1), 58-65.

Hyodo, K., Dan, I., Kyutoku, Y., Suwabe, K., Byun, K., Ochi, G., … & Soya, H. (2016). The association between aerobic fitness and cognitive function in older men mediated by frontal lateralization. NeuroImage, 125, 291-300.

Kwong See, S. T., & Ryan, E. B. (1995). Cognitive mediation of adult age differences in language performance. Psychology and aging, 10(3), 458.

Laird, A. R., McMillan, K. M., Lancaster, J. L., Kochunov, P., Turkeltaub, P. E., Pardo, J. V., & Fox, P. T. (2005). A comparison of label‐based review and ALE meta‐analysis in the Stroop task. Human brain mapping, 25(1), 6-21.

Reynolds, G (2015). Does exercise help keep our brains young? New York Times. http://well.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/12/09/does-exercise-help-keep-our-brains-young/

You Might Like: